Iranian seven colors tiles

With an ancient history and civilization in art and an impressive background in pottery, as well as large reserves of raw materials, Iran was a suitable ground for tile and mosaic industry at the end of the 2nd millennium BC.

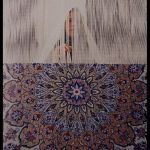

During the Safavid period, mosaic ornaments were often replaced by a haft rang (seven colors) technique. Pictures were painted on plain rectangle tiles, glazed and fired afterwards. Besides economic reasons, the seven colors method gave more freedom to artists and was less time-consuming. It was popular until the Qajar period, when the palette of colors was extended by yellow and orange.[1] The seven colors of Haft Rang tiles were usually black, white, ultramarine, turquoise, red, yellow and fawn.

In the Safavid period, tile craft reached its peak of progress so that the tile-works of Shah Abbas time in Isfahan are still unique in terms of beauty and color stability. An example of this tile-work is present in Sheikh Lotf Allah Mosque in Isfahan which is the world’s most beautiful moaragh.

Safavid mosques and schools are generally decorated with a cover of tiles both inside and outside. While the use of moaragh tiles was ongoing, Shah Abbas, who was hasty to see his incomplete religious buildings, encouraged the use of seven colors tile rapid technique.

In the Safavid era, seven colors tile was largely used in Isfahan’s palaces and installing rectangular tiles inside large frames created exquisite scenes with portrait elements and different personalities.

But oral education and transmission of traditional arts within families or guilds have resulted in elimination of many innovative traditional techniques of tile-setting or tile-work in present time.

The tile is still beautiful and valuable. But nowadays in Iran, the use of traditional tiles is limited to religious monuments or those buildings that insist to pretend traditional. Most of what is built is an imitation of past monuments in a lower level and a trace of creativity can be hardly seen. Spread of Western culture in the native culture and the resulting historical discontinuity has led tile, as a traditional element, not to properly link and function with modern architecture and is mostly considered as a museum issue.