A 128 year old dating service

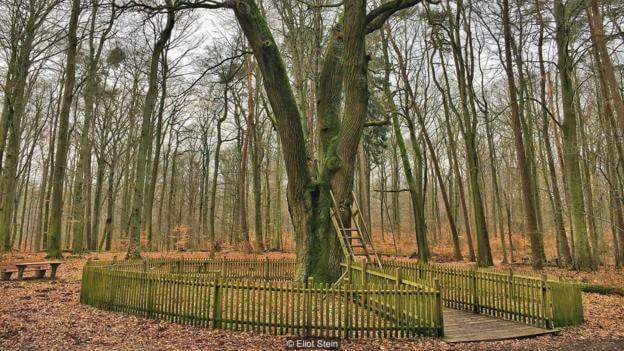

On a chilly afternoon deep in northern Germany’s Dodauer Forest, 100km north-east of Hamburg, a postman wearing a bright yellow uniform was walking alone through the woods. When he reached a clearing, he rummaged through his bag and then slowly climbed a 3m-tall wooden ladder to deliver a purple envelope to a 500-year-old oak tree.

“Just one today,” he told me, before crunching back through the forest and disappearing towards the next letterbox on his route.

The purple envelope was from Denies in Bavaria. She’s 55, isn’t afraid to laugh at herself and loves nature. She knows what she wants, doesn’t mind being alone but wonders if there’s a man out there who can surprise her. If so, she hopes that he, too, is looking for love inside the tiny knothole in this oak tree.

A 128 year old dating service

Known as Der Bräutigamseiche (the Bridegroom’s Oak), this ancient timber outside the town of Eutin has been matching singles long before Tinder, and is reportedly responsible for more than 100 marriages. Today, people from all over the planet write letters addressed to the tree, hoping that for the price of a postage stamp, they may find a partner.

You may also be interested in:

There’s Marie from Brandenburg, who’d like to find a man who can dance; Heinrich from Saxony, who’s searching for a travel partner; and Liu from Shijiazhuang, China, who just wants to know if there’s a German woman who’d like a Chinese friend.

“There’s something so magical and romantic about it,” said 72-year-old Karl-Heinz Martens, who delivered letters to the tree as its postman for 20 years, starting in 1984. “On the internet, facts and questions match people, but at the tree, it’s a beautiful coincidence – like fate.”

A 128 year old dating service

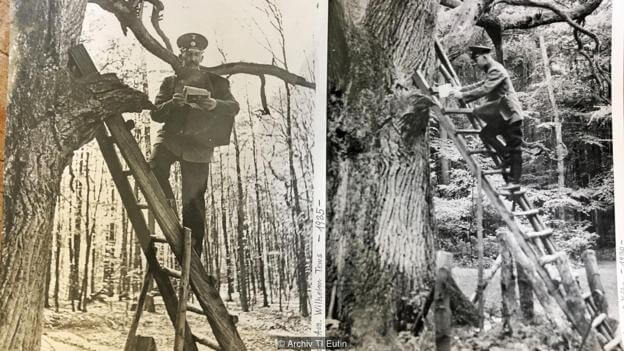

Though retired now, Martens still keeps a scrapbook filled with photographs, letters and newspaper clippings from his time as love’s official messenger – which he happily showed me over coffee in downtown Eutin. In his two decades of service to the oak, Martens delivered letters from six continents, often in languages he didn’t understand. He explained that while today many people know about the tree, 128 years ago it was a secret shared by two lovers.

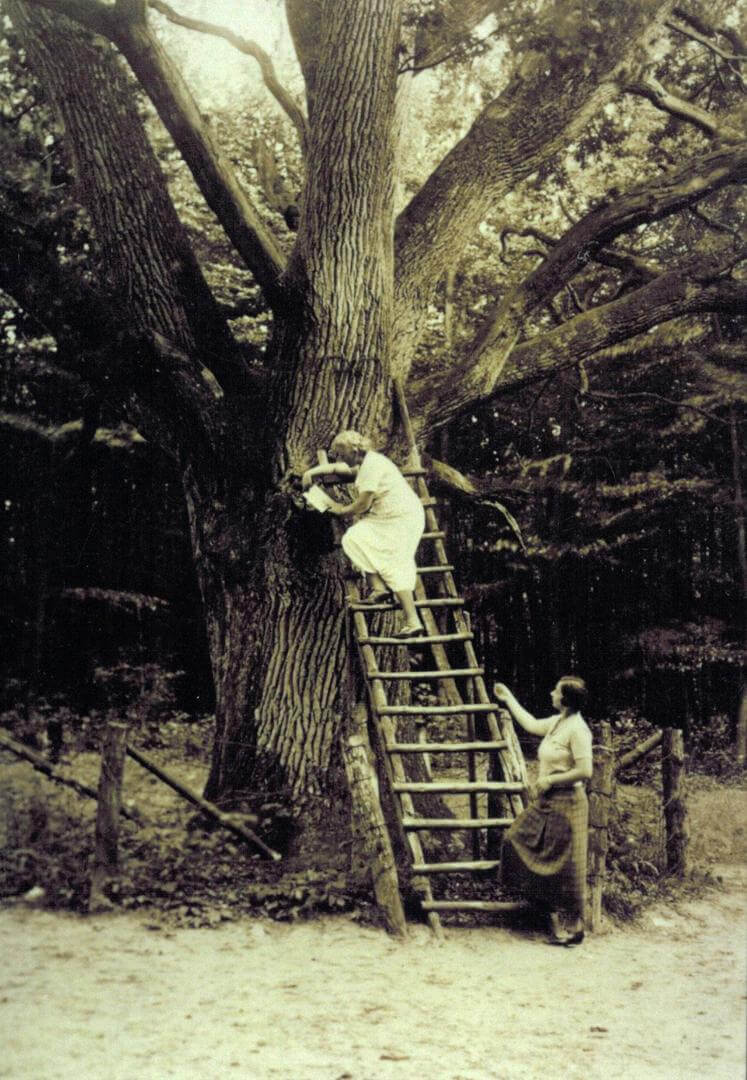

In 1890, a local girl named Minna fell in love with a young chocolate maker named Wilhelm. Minna’s father forbade her from seeing Wilhelm, so the two started secretly exchanging handwritten letters by leaving them in a knothole in the oak’s trunk. A year later, Minna’s father finally granted her permission to marry Wilhelm, and the two were wed on 2 June 1891 under the oak tree’s branches.

The story of the couple’s fairy-tale courtship spread, and soon, hopeful romantics throughout Germany who had no luck finding partners in biergartens or ballrooms began writing love letters to the Bridegroom’s Oak. The tree received so much mail that, in 1927, the German postal service, Deutsche Post, assigned the oak its own postcode and postman. It also placed a ladder up to the fist-sized postbox, so that anyone who wanted to open, read and respond to the letters could.

The only rule, Martens explained, is that if you open a letter you don’t want to answer, you should place it back in the tree for someone else to find.

A 128 year old dating service

“The tree receives about 1,000 letters a year,” said Martin Grundler, spokesman for Deutsche Post. “Most come in the summertime. I suppose that’s when everyone wants to fall in love.”

For those sweet on someone specific, there’s a legend that says if a woman walks around the oak’s trunk three times under a full moon while thinking of her beloved, without speaking or laughing, she’ll marry within the year.

Today the Bridegroom’s Oak remains the only tree in the world with its own mailing address. Six days a week for the past 91 years, a postman has walked through the forest – rain, snow or shine – and climbed the ladder to stuff letters from starry-eyed singles into the tree. And no-one has ever delivered mail to the oak tree longer than Martens.

“It was my favourite part of the day,” Martens said, handing me a black-and-white photo of him wearing a brimmed cap and bifocals, smiling as he dropped letters into the oak. “People used to memorise my route and wait for me to arrive because they couldn’t believe that a postman would deliver letters to a tree.”

In 20 years, Martens said there were only 10 days when no-one wrote to the oak, and while he’d occasionally deliver as many as 50 envelopes a day, not all of them were love letters.

“Before unification [in 1990], people from East Germany who had no contacts in the West used to write to the tree and ask what kind of cars and music we had available,” Martens remembered. “I wanted to write back, but my boss recommended me not to.”

According to Martens, other messages that arrived over the years started as sweet nothings and blossomed into beautiful somethings.

A 128 year old dating service

n 1958, a young German soldier named Peter Pump reached into the oak, felt several letters and pulled out a piece of paper that had just a name and address on it. On a whim, he decided to respond to the ‘Honoured Miss Marita’, who hadn’t written to the tree in the first place – her friends had, knowing she was too timid. Peter and Marita corresponded for a full year before he built up the courage to meet her. They were married in 1961 and are celebrating their 57th wedding anniversary this year.

Then there’s the story of the Christiansens. In 1988, Martens delivered a letter to the oak from a 19-year-old East German girl named Claudia, who was looking for a pen pal. A West German farmer named Friedrich Christiansen found it and wrote back to her. One letter turned into 40, and the couple fell in love. Unable to meet, Friedrich and Claudia exchanged letters for nearly two years across the border. When the Wall fell, the two met for the first time and were married in May 1990.

“I know of at least 10 marriages brought together by the tree,” Martens said. “One, in particular, sticks out.”

In 1989, a German TV station was doing a special feature on the oak, and asked Martens if he himself had ever found love under its branches. He said he hadn’t. A few days later, while Martens was climbing up the ladder to deliver the mail to the Bridegroom, he spotted a handwritten note from a woman named Renate addressed to the oak’s postman.

“I would like to meet you,” it read. “You are my type. At the moment, I am also alone.”

“So I called her – rather clumsily – and soon I met her,” Martens said, handing me a picture of he and Renate kissing on their wedding day. “We were married in 1994 and had our reception under the oak tree.”

The local newspaper printed a photo of Martens on the ladder in his suit and one of the newlyweds kissing under the tree alongside the headline, ‘Wedding of the year’. Twenty-four years later, Martens and Renate remain happily married, and the former postman still keeps her letter.

As the sun began to fade in downtown Eutin, Martens suddenly closed his scrapbook and reached for his coat. “Let’s go before it gets dark,” he said, grabbing his car keys. “Follow me.”

A 128 year old dating service

Fifteen minutes later, I was back in the Dodauer Forest, this time following Martens’ heavy footsteps towards the old oak. At the circular fence around the tree, he pointed towards two signs: one describing the tree’s history, which he wrote; and another reading, ‘May this marriage last a long time!’.

In 2009, after more than 100 years of bringing people together, the Bridegroom’s Oak was symbolically married to a 200-year-old chestnut tree near Düsseldorf. Though 503km apart, the trees remained together for six years until the chestnut started suffering from old age and had to be cut down, leaving the Bridegroom a widow.

“When I started coming here, the tree was stronger and healthier,” Martens said, pointing up to a series of cables securing the oak’s branches. “But I’m not so healthy either, so I suppose we have a special connection.”

Several years ago, arborists detected a fungal infection inside the oak, leading them to lop off a number of its limbs to prevent it from spreading. Around the same time, Martens was diagnosed with leukaemia. Like the tree’s branches, he explained that his bones aren’t so stable anymore.

A 128 year old dating service

But I can still climb the ladder,” he said, slowly raising himself up its rungs.

After peering through the oak’s tiny post box, Martens politely excused himself. It was getting late, and he needed to go back and see his wife.

As he left, a slight man with neatly combed hair carrying a small piece of paper came plodding through the forest. When he approached the oak, I cautiously asked if he wouldn’t mind answering a few questions for a story I was working on.

He said he sometimes comes to the tree by himself after work, and handed me his handwritten note. It read: “I am a widower, 53 years old, 1.75m tall, living in Ostholstein. I’m searching for a slim-medium built loving and loyal partner. Maybe talk soon, Jens.”

A 128 year old dating service

You never know,” he smiled.

I waved goodbye and started walking out of the woods. At the edge of the clearing, I turned to see Jens atop the ladder, sliding something purple into his jacket pocket.