The Native American village of Supai is the most remote village in the lower 48 states, and the only way to reach it is by helicopter or on foot.

Off the beaten path

Roughly 5.5 million tourists visit the Grand Canyon each year, but few realise that this vast abyss is home to a tiny village hidden 3,000ft in its depths: Supai, Arizona. Located eight miles from the nearest road and tucked deep inside a valley at the bottom of Havasu Canyon, Supai is the most remote village in the US’ 48 contiguous states.

The only way to reach Supai is by helicopter, mule or an eight-mile hike through dizzying switchbacks, soaring sandstone pinnacles and sheer cliff drops. In fact, the village is so isolated that it’s the last official place in the US where the post is still delivered by a train of mules each day.

But for those willing to veer off Route 66 in Peach Springs, follow a desolate road 67 miles to the Hualapai Hilltop and walk down a cliff, you’ll discover one of the Grand Canyon’s most sublime secrets: a stunning oasis of five spring-fed waterfalls set against a nearly two-billion-year-old backdrop. Shangri-La? No, this is the ancient home of the Havasupai Native American tribe, which has been quietly living inside one of the world’s seven natural wonders for more than 1,000 years.

The tiny village hidden inside the Grand Canyon

A tiny village in a big canyon

After a four-hour descent through a maze of rust-coloured walls and prickly shrub, the canyon widens and the desert blossoms into a burst of lush green vegetation near Havasu Creek. Welcome to Supai, population: 208.

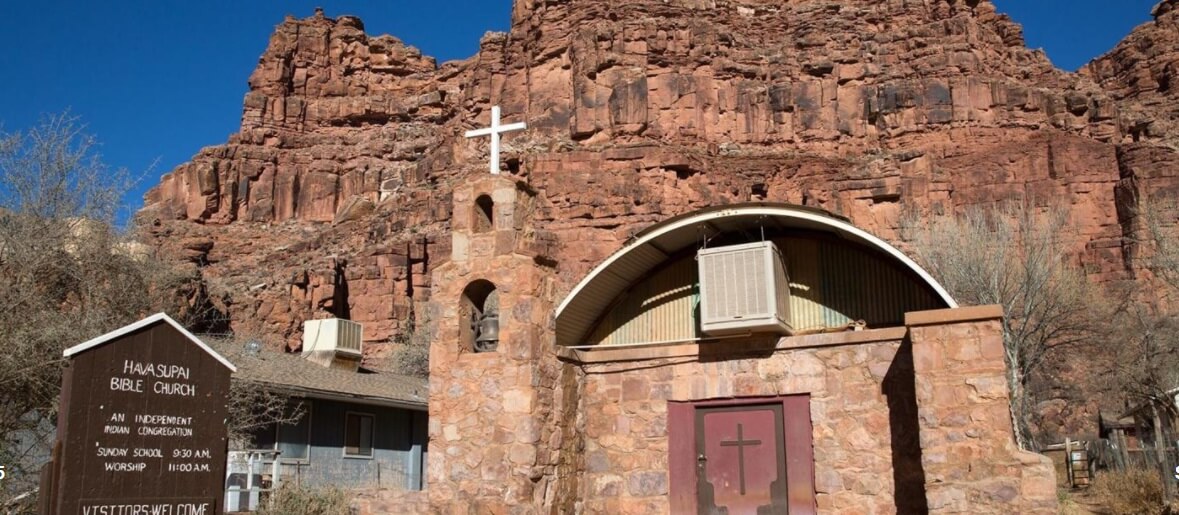

Crossing the creek and stepping foot in Supai feels like being transported to a different time. There are no roads

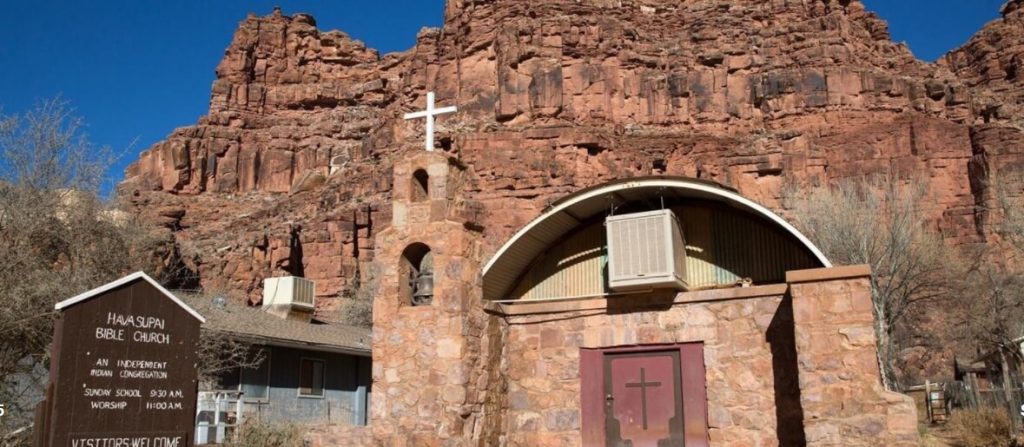

or cars and the only traffic is from villagers leading mules and horses across the dusty canyon floor. A series of homes built from nearby elements surrounds a general store, cafe, post office, primary school, modest lodge and two churches. Residents here still speak Havasupai; grow corn, squash and beans; and weave coiled baskets, just as their ancestors did. And the sound of water – be it from the distant torrent of waterfalls or the nearby trickle of creeks they feed – is never far off.

The tiny village hidden inside the Grand Canyon

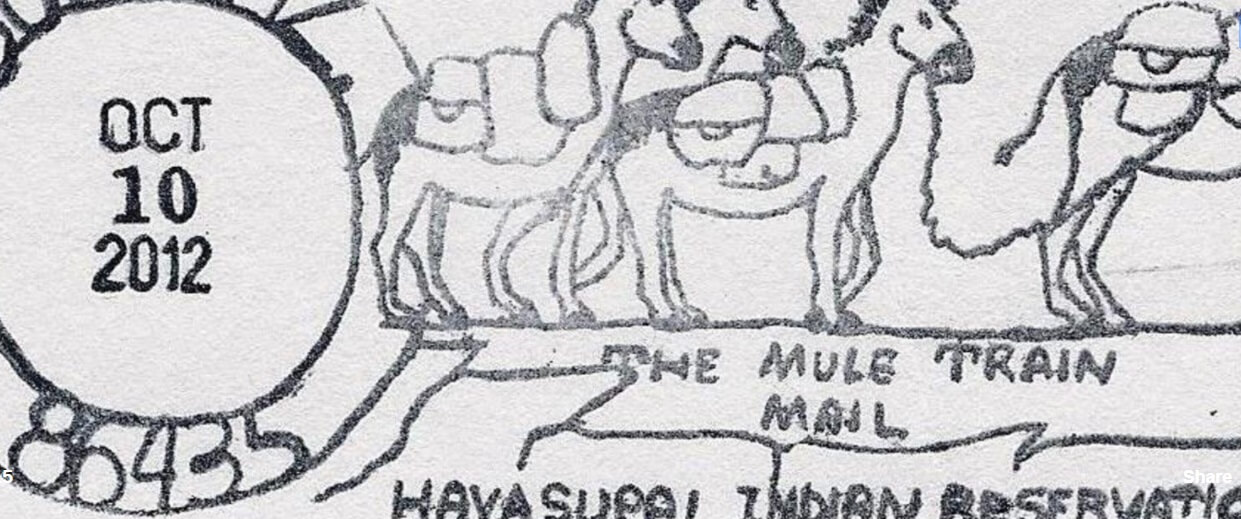

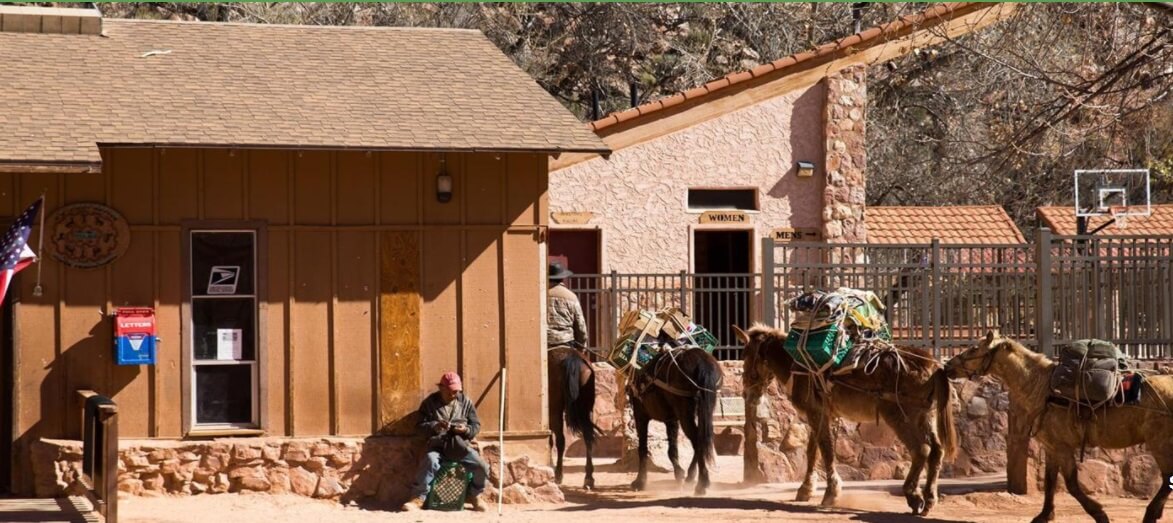

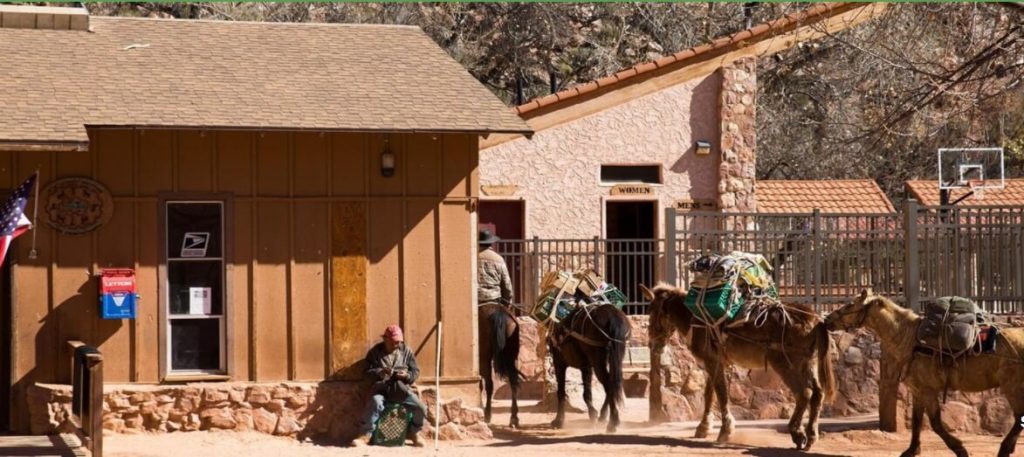

Post-by-mule train

Since Supai isn’t accessible by road, there are only two ways to get supplies down to the village: walk them down

the trail or fly them in a helicopter. The cheapest and most reliable method has always been on foot. So, in an age of speedy delivery, the residents of Supai still receive their post by a train of linked mules.

No-one is precisely sure when the mule train started, but six days a week for as long as anyone can remember, a wrangler has led a hoofed caravan three hours down the canyon and another five hours up. Each item that the United States Postal Service (USPS) sends up and down the dusty trail even comes with a special ‘Mule Train’ postmark.

The tiny village hidden inside the Grand Canyon

The tiny village hidden inside the Grand Canyon

Special delivery

While this post-by-mule route may seem remarkably long as it is, it actually begins 75 miles away from Supai in the village of Peach Springs before sunrise.

Most of the post on the mule train isn’t actually post; it’s food, medicine and other supplies the villagers and its few businesses need to survive. Because Supai is the only village in the US that still gets its post by mule, Peach Springs is home to the only post office in the US with a walk-in freezer.

So early each morning, the USPS loads any groceries and frozen foods Supai’s residents have ordered onto a truck, drives an hour in the pitch-black towards the canyon rim, and loads the rations onto each mule to begin the final leg of the journey down to the village’s post office.

The tiny village hidden inside the Grand Canyon

Changing winds

The Havasupai have always relied on the dusty canyon trail to connect them with the outside world. From missionaries to miners and traders to other tribesmen, a trickle of curious travellers have come and gone over the centuries. But in the mid-1900s, the tribe opened up the trail to backpackers and used its spectacular setting to launch a tourism enterprise.

Today, more than 20,000 visitors hike, hoof or helicopter into Supai – each of whom must obtain special permission from the Havasupai’s Tribal Council to enter. From February through November, visitors can stay in the tribe’s modest lodge or obtain overnight campingpermits to sleep within spray distance of Havasu and Mooney Falls. Those who don’t want to embark on a four-hour hike can swoop into Supai via a four-minute helicopter ride.

The tiny village hidden inside the Grand Canyon

Trouble on the trail?

Over the past few decades, a growing number of voices have spoken out against accounts of mistreatment of pack horses and mules used to haul tourists through the canyon. According to Susan Ash, co-founder of the local organisation Stop Animal Violence, the problem isn’t as much with the USPS, but rather with the lack of enforcement for local commercial wranglers who abuse their animals.

“There are no scales or people checking these animals and the level of suffering is unconscionable,” Ash said. “Temperatures here routinely reach 115F, and some wranglers run their horses and mules up and down eight miles with no water until they literally die.”

The tribe has said accounts of mistreatment were the exception, not the norm. In response, Secretary of the Havasupai Tribal Council, Bonnie Wescogane, said that the tribe has recently employed a team of wranglers to inspect all animals used for commercial purposes and score them on a 1-10 health checklist.

The tiny village hidden inside the Grand Canyon

The tiny village hidden inside the Grand Canyon

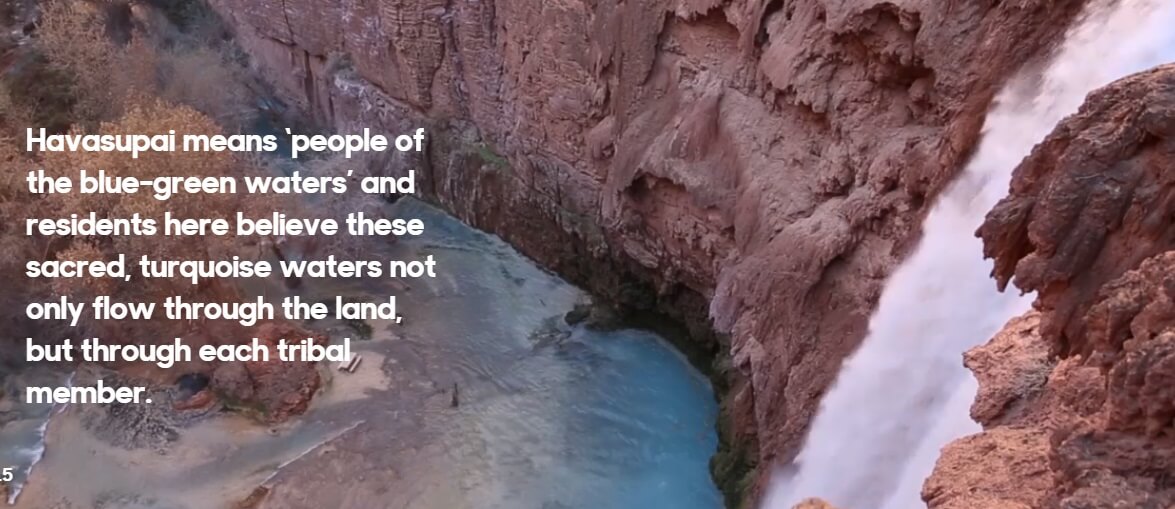

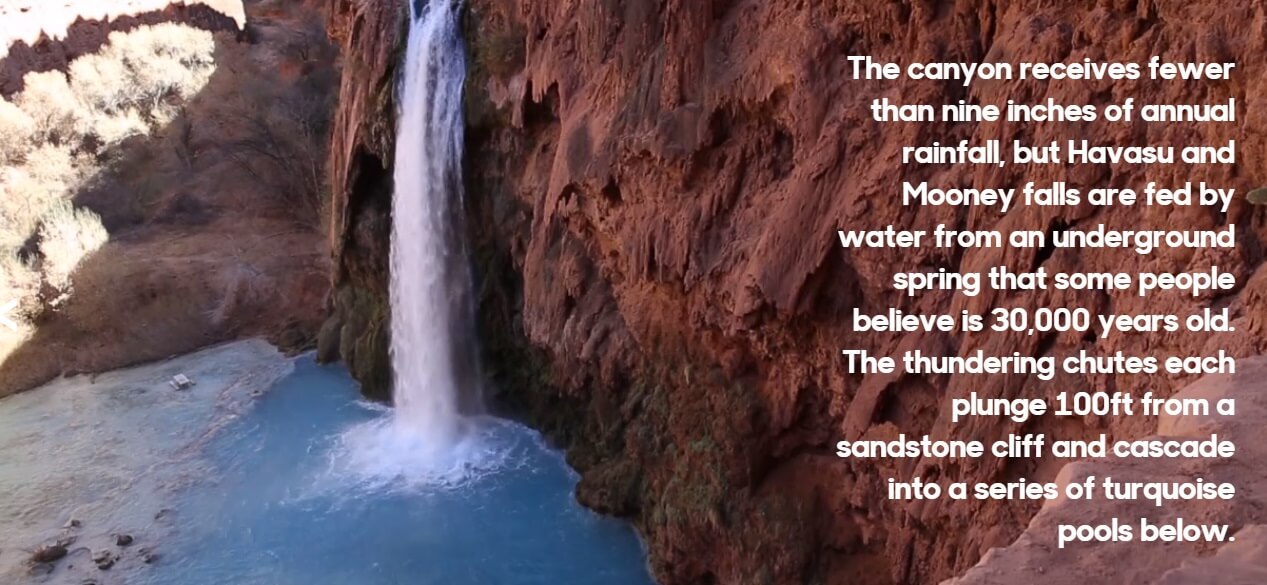

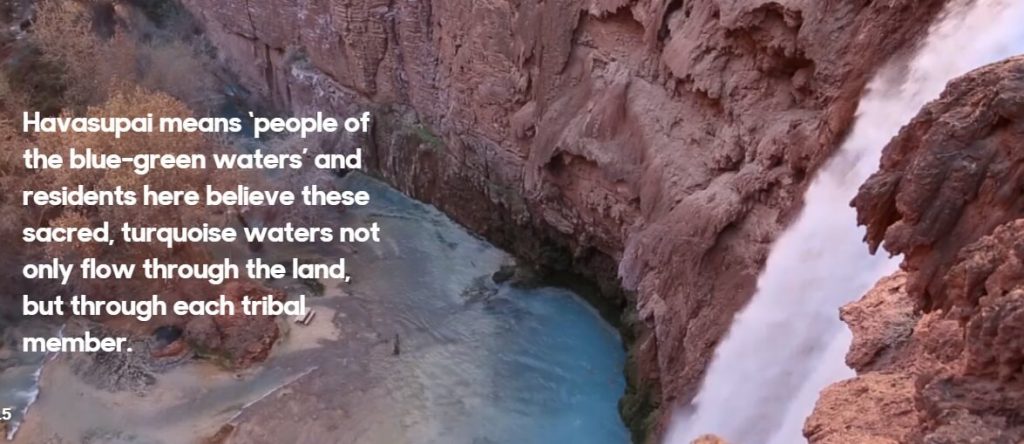

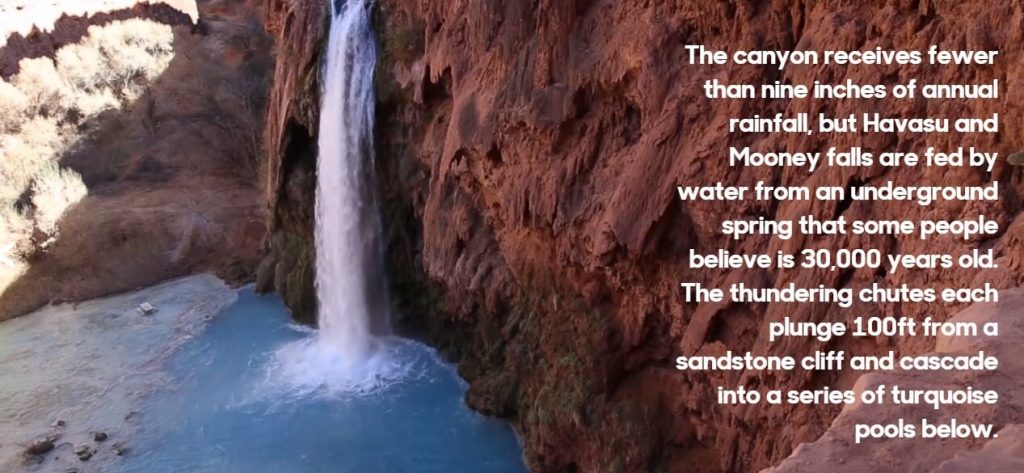

Tropical blue hue

Today, the same life-sustaining springs that have allowed the Havasupai to survive for 1,000 years in the desert are luring droves of backpackers to wade through a series of breathtaking blue pools. Yet, for hundreds of years, no-one knew what gave Havasu’s waters its otherworldly hue – until scientists started digging.

The rocks deep in the canyon floor and below the falls are full of limestone deposits known as travertine. When the travertine-rich spring water meets the air, a chemical reaction occurs and calcium carbonate – the same stuff in chalk – in the water reflects the sunlight above to appear turquoise.

The tiny village hidden inside the Grand Canyon

Proud history of Supai

Before the arrival of European settlers, the Havasupai once roamed a territory spanning 1.6 million acres – roughly the size of Delaware. But as the region’s jaw-dropping beauty and rich minerals began attracting frontiersmen and government interests, this once-vast expanse had dwindled to just 518 acres near the site of modern-day Supai by 1882.

In a period when so many Native American tribes were forcibly removed from their lands, the Havasupai entered into a gruelling series of legal battles over the right to their ancestral territory, appealing to Congress seven different times from 1908 to 1974. When President Roosevelt made the Grand Canyon part of the National Park Service in 1919, many Havasupai strategically became employees of the park and offered their expertise as guides while continuing to lobby for their land.

The tiny village hidden inside the Grand Canyon

Sovereign nation

In 1975, President Ford signed a bill that granted the Havasupai control of an additional 185,000 acres of land, as well as access to 95,000 acres overseen by the National Park Service. Today, the tribe is no longer confined to the bottom of the canyon, but can return to its sacred hunting grounds high atop the plateaus and pine forests each winter.

The Havasupai is now recognised by the US government as a sovereign tribal nation and allowed to govern its own internal affairs. A seven-member committee of elders known as the Tribal Council is elected by villagers to determine everything from local laws to which visitors are permitted to enter Supai.

The tiny village hidden inside the Grand Canyon

Washed away

In recent years, the greatest threat to the Havasupai has been flash flooding. In 2008 and 2010, torrential rains damaged dozens of homes, bridges and buildings and caused hundreds of tourists to be evacuated.

The trail connecting Supai with the outside world was also destroyed in 2010, cutting the village off from its mule train, basic supplies and its tourism economy. In early 2011, the tribe and Governor of Arizona appealed to the US Department of Homeland Security for assistance and received $1.63 million in federal disaster relief.

The tiny village hidden inside the Grand Canyon