Georgia ‘s addictive cousin to pizza

Khachapuri, a gooey, addictive, cheese-stuffed flatbread, is ubiquitous in Georgia. However, most bakers believe that it can only be made properly by happy people.

Khachapuri, a gooey, addictive, cheese-stuffed flatbread, is ubiquitous in Georgia, the Caucasian country that shares borders with Armenia, Azerbaijan, Russia and Turkey. Except for when there’s a funeral.

“If you’re in a bad mood or sad, when you’re grieving the death of a loved one or have a broken heart, you should never even touch dough; just stay away from it,” said my friend Mako Kavtaradze, a born-and-bred resident of the capital, Tbilisi, and executive director of Georgian spice company Spy Recipe. “If you’re not in a happy mood, we will be able to tell when we taste the khachapuri that you make.”

We were eating one of these dairy-and-carb bombs at a roadside restaurant on the Rikoti Pass in central Georgia, not far from the town of Surami, home to an ancient Jewish community. This version was from the nearby region of Imereti: a one-inch-thick, double-crusted wheel of dough stuffed with soft, molten cheese.

But I was doubtful of Kavtaradze’s claim about the connection between human emotions and cheese bread.

To prove her point, Kavtaradze stood up from the table and started walking toward the kitchen. “C’mon,” she said. “I’m going to show you the woman who made this, and I guarantee you she will be as happy as this khachapuri is delicious.”

In the back of the kitchen, a rotund woman was sitting in a chair with a pile of freshly kneaded dough next to her, rolling balls of sallty sulguni cheese for khachapuri. She looked up and flashed a large smile at us, two strangers who probably shouldn’t have just barged into her work space. “See,” Kavtaradze said. “She’s happy.”

Georgia ‘s addictive cousin to pizza

If khachapuri is made by happy people, it also makes its consumers very content. It’s the perfect comfort food.

Georgia ‘s addictive cousin to pizza

In Georgia, one is never further than a ball-of-dough’s throw from khachapuri. Everything from corner bakeries to upscale restaurants serve the snack. And while certain versions of it are pizza-like, a recent poll found that 88% of Georgians still prefer it to pizza. In fact, khachapuri is so popular that economists have coined the term Khachapuri Index, inspired by the Big Mac Index once created by the Economist. In this Caucasian case, Georgian economists monitor inflation by tracking the production and consumption of the main ingredients in khachapuri: flour, cheese, butter, eggs, milk and yeast.

Despite khachapuri’s importance to Georgian cuisine, however, food scholars and historians can’t seem to agree on its origins. But according to Dali Tsatava, food writer and former professor of gastronomy at the Georgian Culinary Academy in Tbilisi, khachapuri could be a cousin to pizza. “Roman soldiers were coming through the Black Sea area and brought with them recipes for something that resembled pizza,” she said as we sat in a cafe in central Tbilisi. “Tomatoes didn’t exist in Europe until the 16th Century, so it was just baked bread and cheese, not unlike khachapuri.”

Nearly all of Georgia’s regions have their own variation of khachapuri, which directly translates as cottage-cheese bread, since the often used chkinti cheese is curdy. I primarily tried the most popular type, Imeruli (from the region of Imereti), which from a distance looks a lot like pizza bianca. But during my week there, I also sampled kubdari at Aripana in Tbislisi, a meat-stuffed version from the Svaneti region; gorged on Megruli khachapuri from the Samegrelo region, which is filled with cheese (like Imeruli khachapuri) and then topped with more melted cheese; and devoured a version stuffed with spinach and potato puree called Khabidzgina khachapuri. It all became a delicious daze of baked bread and cheese made by apparently happy and satisfied Georgians.

Tsatava echoed what Kavtaradze had said earlier: “You can guess the character of the baker who made the khachapuri. It’s like a mirror for one’s emotions.”

But, according to pretty much everyone I talked to, happiness is not the only quality needed for producing next-level khachapuri. As Kavtaradze told me one day while we were walking down Tbilisi’s bustling Rustaveli Avenue, “You have to talk to your khachapuri.” I gave her a quizzical look. “When you’re kneading the dough, for example, you have to verbally finesse it; talk to it like it’s your baby.”

Georgia ‘s addictive cousin to pizza

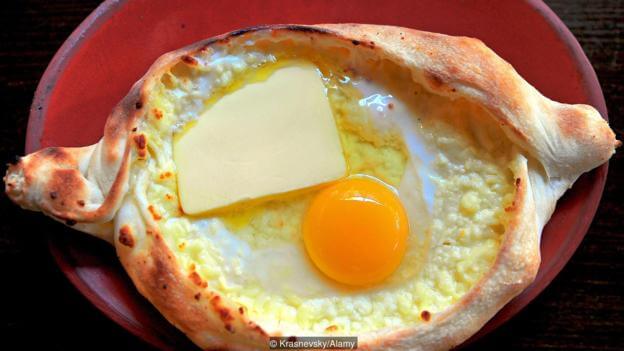

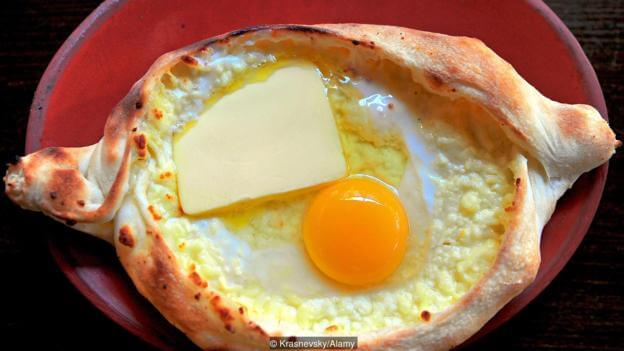

I put this to the test at Sakhachapuren No 1, a subterranean spot in central Tbilisi that is comfy but modern at the same time, where chef Maka Chikhiashvili had agreed to teach me how to make a version called Adjaruli khachapuri. The boat-like shape of the bread, which acts as a basin for molten cheese, is no coincidence. As Chikhiashvili handed me an apron, she said that Adjaruli khachapuri reflects the region’s geography and culture. “Adjara is on the Black Sea, and this is the reason the bread is in the shape of a boat. The egg represents the sun and the cheese is the sea. The people of this region were great boat builders.”

She grabbed a softball-sized hunk of dough and began kneading it, eventually making it flat, as she mumbled away. I asked Kavtaradze what she was saying to the dough. “It’s…” she paused. “It’s too personal. I can’t translate it.”

A few seconds later it was my turn. I took a deep breath and tried to get in touch with my inner tranquillity. I began flattening it out and remembered I needed to talk to it, reminding myself to think of the dough as a baby. “You’re such a good piece of dough,” I said. Everyone in the kitchen nodded in approval. “Who’s a good dough? That’s right; you are!” Eventually I formed the dough into an oval and then tapered both ends. The chef lent a hand to get it into the right shape.

With a long pizza peel, I deposited the flatbreads into the oven. The chef held up five fingers for the number of minutes it should bake for. In the meantime, Chikhiashvili elaborated on the care needed to make khachapuri: “We have five women making our dough and khachapuri here,” she said. “If one or two of them to come to work in a bad mood, they are put on another duty. The dough will be too heavy and not soft or as elastic as it should be.”

Georgia ‘s addictive cousin to pizza

A few minutes later, we were scraping the excess dough from the inside of the partially baked boat, creating a kind of interior rim around the edges. Then we added the cheese, making sure it was nearly overflowing. After going back in the oven for about four more minutes, the only thing left to do was crack a raw egg on top, add a plus-sized dollop of butter, stir it in, and commence eating one of the most delicious things on the planet.

I tore off a piece of the crunchy bread, starting with one of the tapered ends, dipped it into the eggy, buttery, utterly gooey cheese, and took a bite.

I looked at the chef and said, “You must be a very happy person.”

Georgia ‘s addictive cousin to pizza