How sausage flavours the German language

The one that came up most often was the classic ‘Viel Regen bringt viel Segen’ or ‘lots of rain brings many blessings’, which I suspected was less a time-tested truth than a means of consoling an inconsolable bride. My father-in-law, however, only looked at me sadly, shaking his head and repeating ‘Schweinewetter, Schweinewetter’ (‘Pig weather’).

Those concerned with how much we’d invested in the big day might have discussed how I’d spent ‘Schweinegeld’ (‘pig money’ or a lot of money). Still others, in an effort to get me to buck up, could have declared, ‘Alles hat ein Ende, nur die Wurst hat zwei’ (‘Everything has an end; only the sausage has two’).

How sausage flavours the German language

Visitors to Germany love to joke about the country’s obsession with all things sausage, but Germans don’t do anything to discourage them. In fact, their speech is littered with references to Wurst; full of idioms that speak to the timelessness and intrinsic value of their meat products.

As Bonn-based scholar and food writer Irina Dumitrescu detailed in her reprinted 2013 essay ‘Currywurst’, no matter the occasion, the German language will probably have a suitably sausage-y saying for it.“‘Das ist mir Wurscht’ or ‘it’s sausage to me’ is a way of expressing disinterest, perhaps because both ends look and taste the same. Counterintuitively, ‘es geht um die Wurst’ or ‘it’s about the sausage’ gives a sense of urgency: now it really counts. A woman who ‘spielt die beleidigte Leberwurst’ or ‘plays the insulted liverwurst’ is a prima donna in a huff; while someone who can barely steal sausage from a plate – ‘die Wurst vom Teller ziehen’ – is unimpressive despite his pretensions.”

How sausage flavours the German language

Germans also employ common sayings about pigs and swine. As with Schweinwetter, the prefix ‘schwein or ‘sau’ (sow) can be used as an intensifier, and saying someone ‘hat Schwein’ (has a pig) means he had very good luck. I certainly could have used a spare lucky pig or ‘Glücksschwein’ on that wet wedding day.

Statistics from the Bundesministerium für Ernährung und Landwirtschaft (National Ministry of Food and Agriculture) show that the pig is far and away the most popular animal to eat in Germany, with each citizen of the Bundesrepublik consuming 52.1kg per year (in contrast, the Independent reports that poultry consumption in the UK is rising while sales of beef and pork are on the decline). It was all but inevitable that pork would become thoroughly baked into the German psyche, its savoury juices trickling down into everyday language. When and why this started, however, is a bit of a mystery.

“The image of the butcher in Germany is always this fat guy who has two sausages he’s holding up… this rough, laughable figure,” said Hendrik Haase, who has devoted himself to quality, local meat, writing a book on the subject, Crafted Meat; opening Berlin butcher stall and eatery Kumpel & Keule; and founding The Butcher’s Manifesto, which he calls “a rotary club for butchers”.Using humour to deal with a touchy subject isn’t unique to Germany, but it’s central to the way many Germans approach many aspects of their lives. Why should their carnivorous proclivities be any different?

How sausage flavours the German language

“We’re trying to deal with the fact that somebody is killing something for us,” Haase added, “that some animal had to die so you [could] eat a sausage.”

Another theory has to do with the fact that owning a pig used to mean you had a certain amount of wealth and status. “My grandmother had two pigs a year, and she would make sausages, because you’d want to preserve that for as long as you could,” Haase said.

Ursula Heinzelmann, food scholar and author of Beyond Bratwurst: A History of Food in Germany, explains it as a difference between farming and roaming peoples: “If a culture keeps pigs, that’s a sign that they have settled down and are not nomadic anymore. Let’s say that’s the difference between Europe and [certain groups in] northern Africa or the [Middle] East.”

How sausage flavours the German language

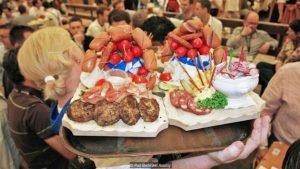

Eating sausages can also help form a sense of camaraderie. No German institution promotes this quite as well as the beer hall or Biergarten, where sausages are always on the menu. In Germany even today, food is often more about ritual and gathering, less about taste.

In their quest to be frugal, Germans often value price over flavour as well – and rarely do the two come together as successfully as they do in the humble Wurst. “We figured out a long time ago that [conserving] was best done by stuffing all those little bits and pieces, including the offal, into the casings,” Heinzelmann explained. It isn’t fancy, it isn’t refined, yet it defines what it is to be German – to want to save every last bit of the treasured pig.What’s more, writes Neil MacGregor in his book Germany: Memories of a Nation, each part of Germany had its own sausage: “Wurst, like beer, defines Germany’s cities and regions, each different sausage with its own ingredients and particular traditions…. A Wurst map of Germany would be a mosaic of ungraspable complexity.”

How sausage flavours the German language

It can’t be a coincidence, then, that the names of several meat products have endured. Wieners, Frankfurters and even the humble Hamburger all are simply names of German-speaking cities, and of people from those cities. One can almost imagine the smooth little sausages from Vienna (Wien) or Frankfurt, practically bursting their casings with pride at hailing from such illustrious places. Those eating them – perhaps laughing over Wurst-laden speech to signal their belonging to this multi-faceted yet unifying culture – might feel a similar burst of pride as they downed a beer and bit into a sausage named for their hometown.

For our part, we served no Wurst at our wedding, but we did have something even better; something I consider so German, it gave the whole ceremony, damp and muddy as it was, an almost medieval bent: a wild boar roasting on a spit, which guests were invited to sample at their leisure.

Perhaps it was the Glücksschwein we needed after all: Seven years later, no-one remembers the weather, but everyone is still talking about the food.