Where doing nothing is a way of life

Dalmatia’s fjaka state of mind

One hot July, I was sitting at a cafe in Dubrovnik waiting for someone to show up with keys to the apartment I was renting. It had been over an hour.

“Excuse me, have you seen Pero?” I asked the waiter in Croatian. “I am supposed to meet with him, to get keys to an apartment.”

“He is probably on fjaka,” the waiter said, shrugging.

Frustrated, I wanted to throw my hands up in the air. As an impatient New Yorker who always wears a watch, I was driven crazy by his lateness.

Where doing nothing is a way of life

Apparently, there was a wave of fjaka going around, brought on by the high temperatures that summer. Pero eventually showed up with the keys after an hour and a half, without any explanation or apology.

By then, after a few trips to Dalmatia, a region of Croatia along the Adriatic Coast, I heard more about this word ‘fjaka’, but I had yet to grasp the concept, let alone try to accept it. My family’s roots are from Karlovac, near Zagreb, where the Austro-Hungarian influence imparted a different mentality.

As a local explained to me, fjaka is a sublime state in which a human aspires for nothing. Fjaka is something that can’t be learned; in Dalmatia, it’s considered a gift from God. And one must experience it to awaken its meaning. Various Dalmatians I spoke with over a dozen visits explained that fjaka is an elusive concept that is experienced in different ways.

Half somewhere and half nowhere

Where doing nothing is a way of life

The first time I surrendered to fjaka was while studying the Croatian language in Dubrovnik in August 2004. It was during calmer, pre-tourism-boom times, before the medieval-walled city was a set for Game of Thrones and Star Wars. It began when I could hear the clicks of my flip-flops against the centuries-old cobblestones slowing down. I remember sitting at Café Festival on Stradun, the main artery of the Old Town, out of which lanes branch like a stick tree. Under the awning, which did little to shield me from the intense Mediterranean sun, I sipped bijela kava (white coffee) and sweated through my clothes, people-watching and scribbling in my journal for hours that easily slipped by.

The oppressive heat and boiling Mediterranean sun brought about the languor inherent to fjaka; I felt I was being slowly beaten by the high summer temperatures. Eventually, I could barely lift my pen to the page, and my thoughts flitted by like the čiope (swifts) darting across the sky, their scythe-like wings carving through the cloudless expanse of blue. Fjaka caught me in her hot jaws like a phrase I later learned, “Ajme, judi, ufatila me fjaka!” (“Alas/Damn it, my friends, fjaka has caught me!”). My energy sapped, I felt unable to work.

The Croatian poet Jakša Fiamengo said that fjaka is a specific state of mind and body. “It is like a faint unconsciousness,” he wrote, “a state beyond the self or – if you will – deeply inside the self, a special kind of general immobility, drowsiness and numbness, a weariness and indifference towards all important and ancillary needs, a lethargic stupor and general passivity on the journey to overall nothingness. The sense of time becomes lost, and its very inertness and languor give the impression of a lightweight instant. More precisely: it’s half somewhere and half nowhere, always somehow in between.”

Croatia has been always somehow ‘in between’. Sandwiched between the Adriatic Sea and Montenegro, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Serbia, Hungary and Slovenia, present-day Croatia has been a point of conflict between East and West. Most recently, the 1990s war in Yugoslavia fractured a complex country that was comprised of similar yet distinctive Slavic areas, divided over ethnic, religious and geographic lines.

Where doing nothing is a way of life

Located on the central eastern Adriatic Coast, Dalmatia has a unique regional identity within Croatia and a laid-back Mediterranean vibe. In the Middle Ages, the core of the Croatian state was formed in the historical Adriatic regions of Liburnia and Dalmatia. Geographic borders were often disputed and changed over time, mirroring the tumultuous region and disparate cultural influences. Most of the Dalmatian cities (today, Dalmatia’s largest cities are Zadar, Šibenik, Split and Dubrovnik) were long-time possessions of the Venetian Republic, a sovereign state and maritime republic in north-eastern Italy, which ruled for 400 years from across the Adriatic Sea.

The Italian influence is still apparent in Dalmatia. Many Dalmatians sprinkle Italianesque words into Croatian sentences, which were adapted to the region’s Slavic roots. It is no surprise, then, that fjaka derives from an Italian word, fiacca (weariness) – but fjaka doesn’t have an adequate translation. The Dalmatian fjaka is a cousin to the classic Italian saying dolce far niente (it is sweet to do nothing), but it is not the same. Dolce far niente has a positive connotation, while fjaka is not necessarily bad or good. It exists, as Fiamengo says, somewhere in between.

Summer slowdown

During my visits, starting in 2000, I observed that while tourists basked under the relentless afternoon sun, Dalmatians would often retire indoors or to a shady spot for the equivalent of a siesta – a regenerating summer habit that replenishes the body and mind. I became comfortable with unproductive afternoons spent in the shade, allowing fjaka to wash over me like a soft Mediterranean breeze. When stores were closed, I accepted the response, “He is on fjaka.” I grew to appreciate the slower Dalmatian pace. The relaxed attitude encouraged me to take one day at a time.

Where doing nothing is a way of life

Igor Zidić, an art historian and critic from Split, says fjaka is an essential and unique part of the Dalmatian character. “Fjaka is, among other things, a way of survival: it does not exist in the regions of western or northern Europe, and its related phenomena are recorded throughout the Mediterranean zone where summer temperatures [can] reach 40C,” Zidić said. “Of course, to those who are more vulnerable to it, the fjaka shapes their actions and behaviour, affects their jobs, their lives.”

“I was probably one of those who were born in fjaka, in my mother’s womb. Fjaka is part of my personality,” said Dino Ivančić, a Split tour guide and former professor of history and Italian language and literature, whose family roots in Split stretch back generations. When Ivančić pictures a man in the state of fjaka, he is stretched out in a hammock by the sea under the shade of a tree with a full bottle of wine within reach, a fish line tied on his toe.

Fjaka also features in the song Smoči svoj… (u more prst) – Get wet yours… (finger in the sea) – by Split singer-songwriter Toma Bebić. “He is saying that because of the fjaka, we did not want to go anywhere but we brought the rest of the world to our beautiful Split,” said Ivančić. “When you have fjaka, you don’t even want to travel. That’s why he’s singing to get [your finger] wet, and then you’ll have contact with the rest of the world, and this is enough.”

Moment of a lifetime

Some summer days in Dalmatia, even dipping my finger in the sea seemed like a momentous feat, requiring energy from reserves I didn’t seem to possess. I acutely felt fjaka’s fatigue, slowness and drowsiness, but appreciated that life was organised as the weather dictated. I wanted to share this state with my then-boyfriend when he first visited Dubrovnik in 2007. I was convinced Jaidev would intuitively understand. As a Punjabi who jokingly refers to ‘Indian Standard Time’, where arriving to dinner more than an hour late is the norm, I imagined he’d embrace the concept without resistance.

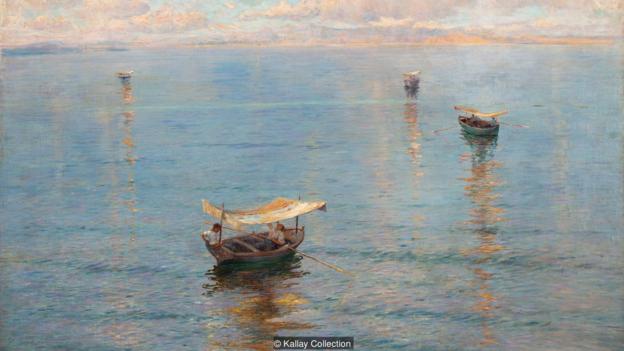

We hired a boat and skipper and ventured out to sea, stopping for a swim and a two-hour-long lunch with fresh fish on an uninhabited island. He’d taken his briefcase aboard, which I found amusing, since I knew we would both surely succumb to fjaka with the combination of the sea, sun and prosecco.

Where doing nothing is a way of life

What I didn’t know was that in his briefcase was a ring. He roused me from my afternoon slumber on the bow with a proposal. He said, “Do you want to spend the rest of your life with me?” I answered yes. Opening the box, he said, “Marry me.” We were wed two years later in Dubrovnik.

Fjaka played an indelible part in our lives. That day, with the sun sparkling on the waves like a blanket of diamonds, will forever be etched in my memory. Everything felt as if it could wait.

Zidić recently introduced me to a dialectological dictionary that captures fjaka in an example of conversation: “The sun was blown, the sky and the earth were burning: it was boiling, so we were taken by fjaka, and we are lying under the bow of the ship and the work can wait.”

In stressful times I keep the image of our engagement tucked in my mind. The two of us lying on the bow of the ship. The two of us under the spell of the strong Dalmatian sun. The two of us surrendering to fjaka.

Where doing nothing is a way of life