The last beekeepers of Ethiopia’s Harenna forest

The sun was beginning its evening dip as I set off into the Harenna Forest. Strange tubular shapes glowed in the treetops, catching the pale golden light.

Wedged between branches, they looked like elongated wine barrels or giant cocoons.

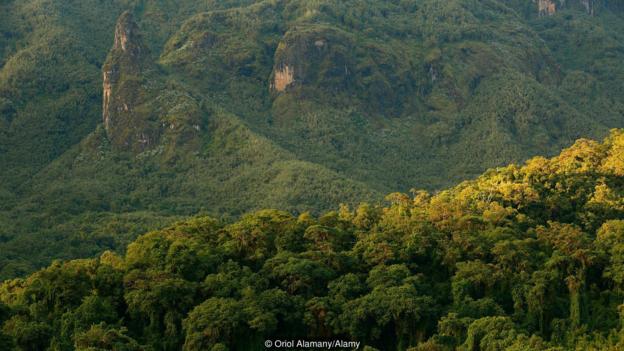

I was en route to witness a unique honey harvest in the forest. Here, on the southern slopes of Bale Mountains National Park in south-east Ethiopia, hand-carved beehives are placed high in the tree canopies. Reaching them to retrieve the sweet, sticky nectar is arduous – and often dangerous.

Local guide Ziyad and I followed beekeeper Said over a flower-strewn meadow before being swallowed into a tangle of trees.

Ethiopia’s dangerous art of beekeeping

The Harenna Forest is straight out of a children’s storybook. Giant heather and fig trees, elegantly clothed in emerald moss, stretch out their branches as though frozen mid-dance. Black-maned lions roam the area, which is also home to olive baboons, warthogs and endangered Bale monkeys. On our walk, a white-cheeked turaco fixed us with its orange-rimmed eye, striking against pickle-green plumage.

Said began preparations, gathering handfuls of moss and lichen, wrapping the bundle with twine and lighting it to create a glowing bouquet for smoking out the bees.

A curious colobus monkey watched nearby as Said scaled the Hagenia abyssinica, a native tree whose sturdy branches and vast, umbrella-shaped crown provides a secure, sheltered home for the hives. He was barefoot and equipped with a single rope – a luxury not all local beekeepers can afford.

Ethiopia’s dangerous art of beekeeping

He shimmied up a few metres at a time, pausing every few minutes to loop the rope higher up the broad trunk. The hive was around 20m above the ground. Finally, straddling a branch, he inched towards it and blew smoke from his mossy torch into a tiny hole in the hive, releasing a flurry of glowing embers into the air.

Said is one of a handful of beekeepers to still use this ancient method of beekeeping. While other parts of Ethiopia are moving to more modern production, the 600 families of the Harenna Forest are reluctant to abandon techniques honed over generations.

Their hives are made from the hollowed-out trunks of dead trees, carved in two canoe shapes and woven together with strips of bamboo. Before being suspended in the treetops, they are smoked over a fire stoked with beeswax and moss, infusing them with an aroma that attracts the queen.

It takes three days to make a hive, and two people to winch it high in the trees. Once there, each can last up to eight years, yielding around 5kg of honey each biannual harvest, usually June and December.

After smoking out the swarm, beekeepers reach inside to retrieve the combs, squeezing the golden liquid into toughened leather pouches.

Ethiopia’s dangerous art of beekeeping

Timing is everything.

Minutes after reaching the hive, Said released a sharp yelp. Within seconds, he’d slithered down the trunk and was back on the ground. It was too early. A relatively cool summer had delayed hatching, and baby bees – or ichs – were still curled in the honeycombs. The nibi, or adult bees, were angry. They continued attacking as Said stumbled away from the tree, shielding his face with a gossamer-thin scarf.

“Beekeepers often can’t collect [the honey], and then they have to wait for the right moment to go back up,” Ziyad explained patiently, painstakingly plucking bees from Said’s hair and clothes.

Stings might be common, Said added, but this time he’d been assailed by “more than 100 bees”. This had happened just twice in his 10 years as a beekeeper.

With 70 hives clustered in this spot of the forest, Said comes from a line of beekeepers stretching back more than a century. Honey is the second biggest source of income after coffee, which grows wild here. They sell tubs of honey at local markets, keeping some for tej, a mead brewed with freshly harvested honey, water and gesho, a native species of buckthorn used to balance the sweetness with subtle, earthy spices. Every family has its own recipe, bringing out gourds of the wine on special occasions. No celebration is complete without tej.

Ethiopia’s dangerous art of beekeeping

Leaving a forlorn Said by his hut, we trekked back to Bale Mountain Lodge, whose thatched chalets are dotted about the Katcha clearing, overlooked by Mount Gujuralli.

“Generations have been making honey like that,” Guy Levene, who co-owns the lodge with wife Yvonne, told me. The lodge organises tours to see the honey harvest and is keen to help the Harenna beekeepers earn more money from their craft.

Levene has even been looking into ways to sell the delicately flavoured syrup abroad, while Slow Food Foundation – an offshoot of Italy’s Slow Food Movement – works with beekeepers in pockets of Ethiopia to help increase production, providing bigger, grounded hives and modern machinery to extract honey from the comb.

Ethiopia’s dangerous art of beekeeping

Ethiopia’s dangerous art of beekeeping

Here in Harenna, however, beekeepers are reluctant to abandon generations of tradition, no matter how labour intensive, and hazardous, it might be.

There is method in the madness. Placing the intricate hives high atop trees increases the bees’ chances of finding them as they zigzag through the forest. The height also creates distance from creatures that might disturb the hives and snaffle the contents, such as snuffling honey badgers. A few trees wear scraps of metal, like armour, for extra protection from tree-climbing bandits.

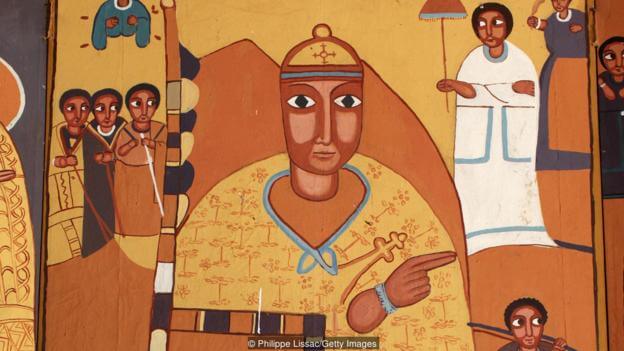

But it’s not just about practicality, or even profit. In Ethiopia, honey trickles through centuries of culture and religion. It features in 4th-Century Christian frescoes and tapestries, where saints are seen clutching bereles, the traditional fat-bottomed flasks used for serving tej. Lalibela, the town 1,100km north of the Bale Mountains that’s famous for its 13th-Century monolithic churches, even translates as ‘honey eater’. It’s named after King Lalibela who, according to legend, was swarmed by bees as a newborn, miraculously emerging unscathed. His mother named him Lalibela, declaring the bees had recognised him as a ruler.

Ethiopia’s dangerous art of beekeeping

Honey here is healing, even spiritual. Folklore says that bees constructed hives – chewing wax until soft, then bonding it to create honeycomb cells – in the windows of Lalibela’s earliest churches before the first congregation in 488AD. They still produce ‘holy honey’ or mar, reserved only for healing – applied topically to treat skin diseases or, for internal illnesses, eaten by the spoonful or imbibed with holy water.

In the Bale Mountains, honey is both part of everyday life and a symbol of social status. Families with larger numbers of beehives and a higher yield of honey are held in high regard. Ownership is sacred, and theft of other beekeepers’ honey or hives is rare: if caught, the culprit is shunned by his neighbours.

Spoonfuls are taken in the morning, the antibiotic properties believed to ward off illness and soothe the soul. Bees pollinate up to 20 different plants, resulting in a complex, perfumed honey. Nectar gathered from Hagenia trees, whose dusky pink blooms are brewed into a tea to treat tapeworm, adds medicinal value.

The day after the harvest, guide Ziyad took me to his village, Rira, a brief but bumpy drive along pot-holed paths.

Slow Food Foundation formed a beekeepers’ cooperative here in 2014, aiming to refine the honey collection and packaging process so a more sophisticated product can be brought to market. It’s a slow process. As in the Harenna Forest, Rira’s beekeepers are attached to traditional methods. Many families have hung their hives in the same trees for several generations. For now, the priority is providing and encouraging the use of protective clothing and equipment, to at least minimise the risk of injury.

Ethiopia’s dangerous art of beekeeping

In the tiny village, we sat on plastic chairs surrounded by teardrop-shaped huts cladded with mud and woven with straw, as plates appeared from a tiny kitchen.

Finally, I got to taste the dark amber honey – creamy, fruity and floral, with a whisper of smoke – mopped up with ambasha flatbread. Groups of children sat nearby, devouring the same.

Honey and bread is a regular after-school snack, Ziyad explained. Leftover bread is chopped up and mixed with more honey, then eaten in bowlfuls for breakfast.

“It’s always been that way,” he said. “Honey with everything.”