Macaroni cheeses mysterious origins

There was a bite in the cold Alpine fog lingering over the resort town of Fronalpstock in Switzerland’s Canton Schwyz. I wiped my wet boots on the mat and entered Gipfelrestaurant Fronalpstock, a wood-lined mountain tavern on the edge of the snow-capped Schwyzer Alps that overlooks the eerily turquoise Urnersee. I’d been trekking up and down steep switchback trails most of the morning; my legs were aching and my stomach was growling. Before I even opened the lunch menu, I knew exactly what I was going to order: Älplermagronen, the Swiss version of macaroni cheese.

Macaroni cheeses mysterious origins

The dish, which translates to ‘Alpine herder’s macaroni’, is ubiquitous on restaurant menus from Appenzell to Zermatt. And, as most Swiss will tell you, it tastes better when you’ve earned it, as I had hiking that morning.

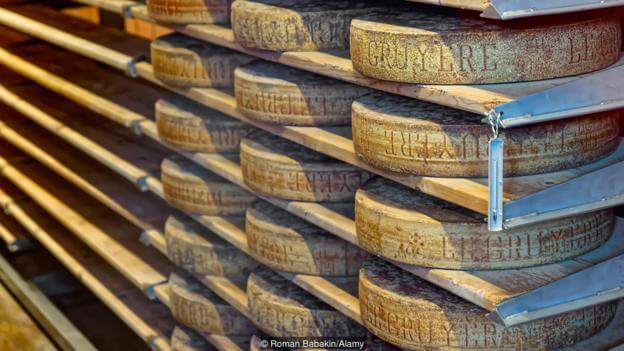

Älplermagronen is usually made with elbow macaroni, locally called magronen or hörni, because it’s shaped like the horns of native chamois and ibex. The pasta dish is fortified with cream and gooey melted cheese – often AOP-protected Gruyère from western Switzerland, but sometimes local alpine cheeses made from cows grazing the very same mountain it is served on.

“Älplermagronen got its name because the shepherds who lived on the alp with their cows had to carry up all their own food,” explained Paul Imhof, author and food historian of Das Kulinarische Erbe der Schweiz, a five-volume set of books on the history of Swiss cuisine published in 2017. “Dry pasta is light to carry; cheese [the shepherd] made himself. So here in Switzerland, there’s a logistical reason behind this simple dish.”

Älplermagronen, called ‘Macaroni du Chalet’ in French-speaking Switzerland, varies from canton to canton; the version that arrived at my table was teeming with potato slivers and topped with crunchy roasted onions. Although it lacked the slices of smoky bacon or ham often found in the dish, it was smartly served with a cold, sweet ladleful of apfelmus (apple sauce) to cut through the stodginess. It was not the best I’d had, nor the worst. But it was warm and restorative – and as natural a fit to the Swiss Alps as cow bells, gondolas and yodels.

Macaroni cheeses mysterious origins

Many countries have a profound love and deep historical connection to a version of this dish – including the United States, Canada, the United Kingdom, France and of course Italy, where pasta was first popularised in Europe. But with a trail of clues pointing to the Alps, it’s possible that macaroni cheese’s origins may in fact trace back to Switzerland.

Americans especially love to claim macaroni cheese as their own, and indeed Kraft invented the boxed version using macaroni in 1937 at the height of the Great Depression, helping popularise it worldwide. But neither cheese nor macaroni were invented in the US, and tracing the dish takes us back centuries and to several accounts about its possible origins.

The word ‘macaroni’ has meant different things to different people over time. It appears in several old cookbooks, but none provide conclusive evidence of how, when or where the macaroni cheese dish evolved into the pasta bake of modern day. The International Pasta Organisation traces the word ‘macaroni’ to the Greeks, who established the colony of Neopolis (modern day Naples) between 2000 and 1000BC, and appropriated a local dish made from barley-flour pasta and water called macaria, possibly named after a Greek goddess.

Liber de Coquina, a cookbook published in the beginning of the 14th Century by an anonymous Neapolitan, contains a recipe for ‘de lasanis’, sheet noodles cut into 5cm squares and sprinkled with grated cheese. While historians believe this is the first time that pasta and cheese appear together in print, it’s hardly the molten-centred dish we know and love today.

Macaroni cheeses mysterious origins

England’s oldest cookbook, Forme of Cury, written by King Richard II’s cooks in 1390, has a Middle English recipe for something called ‘Makerouns’, but the recipe is more lasagne-like: “Make a thynne foyle of dowh, and kerue it on pieces, and cast hym on boiling water & seeþ it wele. Take chese and grate it, and butter imelte, cast bynethen and abouven as losyns [lasagna].”

Flash forward nearly 500 years to 1861: the famous and authoritative Victorian cookbook, Mrs Beeton’s Book of Household Management, contains a recipe for macaroni cheese that’s somewhat similar to today’s dish, calling for parmesan or Cheshire cheese and breadcrumbs to be toasted on top of crooked pipe-shaped noodles (more like today’s bucatini than short macaroni elbows). More interesting, Mrs Beeton waxes poetic about this ‘macaroni’ and claims that it’s ‘a favourite food of Italy’, where ‘Neapolitans regard it as a staff of life’.

This Neapolitan macaroni cheese lineage theory was supported a decade later by French gourmand Alexandre Dumas, who stated that Naples was the homeland of macaroni cheese in his Grand Dictionaire de Cuisine, posthumously published in 1873. But he took it a step further, crediting Catherine de Medici as a likely source of how the dish spread north after she moved from cosmopolitan Florence to France in the 1530s to marry King Henry II, bringing with her many food innovations from across Italy. Funnily enough, Dumas himself was said to despise the dish, calling the noodles ‘long pipes of pity’ and even entering a feud over them with Gioachino Rossini, the Italian composer of the William Tell Overture (an homage to the Swiss folk hero) and a devout macaroni cheese fanatic. The spat happened after Dumas asked Rossini to prepare the dish for him, but then refused to eat it.

Macaroni cheeses mysterious origins

But there’s a potential hole in the Neapolitan lineage macaroni cheese theory, one that suggests Beeton and Dumas might have been wrong about attributing the hallowed dish to Naples. Pasta was indeed popular in Naples in the 17th and 18th Centuries, according to National Geographic, for three main reasons: wheat was cheap, pasta-making became industrialised, and the church prohibited meat on certain days, making pasta a filling substitute. But pasta consortiums and unions in Italy, known for their extensive records of various pasta shapes, had no records of a hollow pasta in Naples in the 14th Century.

So, where did the macaroni pasta shape come from?

According to Imhof, the first published record of macaroni was in the 15th Century by author and epicure Maestro Martino from Valle di Blenio in the Duchy of Milano, Lombardy, in what is today Ticino, the Italian-speaking part of Switzerland. Martino’s landmark cookbook Libro de Arte Coquinaria, published in the 1400s, contains several macaroni dishes, including instructions on how to make the hollow tube pasta by wrapping the dough around a stick, as well as recipes for ‘Maccaroni Romaneshi’ and ‘Maccaroni Siciliani’, both of which are served from boiling pot to plate and garnished with butter, sweet spices and cheese

Macaroni cheeses mysterious origins

.

These recipes are the first that begin to resemble the macaroni cheese we know and love today. But like Beeton and Dumas’ pipes, the noodles used were much longer than the short elbow macaroni now favoured. And while macaroni recipes from Sicily, Naples and Rome were abundant after the 1700s and often called for cheese, they veered toward Byzantine flavours, often including sweet spices like cinnamon, rosewater and sugar. While up north, near the Alps, the dish was taking a humbler, heartier turn, often simplified to include just pasta, cream, butter and cheese.

“In the 15th Century, the neighbouring canton of Uri and other central Swiss cantons took over parts of Ticino [from Lombardy] so the trade between Switzerland and Lombardia was frequent,” Imhof said.

By 1731, Switzerland’s Disentis Abbey (about 50km from the Italian border) mentions in its archives a thread press machine to make hollow macaroni noodles. In 1836, a cookbook from Bern published a recipe for ‘Maccaroni’ that called for Parmesan or Swiss Emmental cheese and oven-baking. Two years after that, according to Imhof’s book, Switzerland’s first pasta factory opened in 1838 in Lucerne. And finally, according to Imhof, the world’s first commercial production of macaroni as we know it today – the short, hollow, hörni-shaped elbow – was not in Italy, but in Switzerland in 1872. Add to this a Swiss cheese production and export culture that dates back millennia, and it’s certainly possible that the first real macaroni cheese with hollow elbow noodles was served in Switzerland.

Macaroni cheeses mysterious origins

Whatever the truth, this humble pasta-with-cheese dish has become an ultimate comfort food in a plethora of cultures and countries around the world, each with their own favoured tweaks. But for me, after my hike in the Alps, few dishes could be as satisfying as the Swiss version in front of me.

As I sat atop the mountain, refuelling on this king of carb bombs and watching the nearby cows munch on wildflowers, as they have for millennia, I felt certain this dish will be around for a long time to come.

travel to Iran, trip to Iran, Iran tours, Iran traveler, Iran travel agency, Iran tour operator, Iran visa, Iran travel news, travel, traveler, Iran accommodation, Iran hotel, Iran flights, Iran local travel agency, Iran destination, Iran visitors, Iran trip adviser, trip adviser, Iran safety, Iran hotel, Travel news, Iran travel news, Iran cultural tour, Iran cultural tour, Iran classical tour, Iran natural tour, Iran nomad tour, Iran historical tour, Iran eco tour, Iran booking hotel