An ancient word no-one can translate

With only one remaining fluent speaker, the Yaghan language is on the verge of dying out. Will this obscure word be its sole survivor?

It was spring when I reached the end of the world. On that mid-September day it was cold and raining in the city of Ushuaia, Argentina, but the sky cleared as I trekked nearby Tierra del Fuego National Park, allowing the sun to reflect off crisp glacial waters and snow-covered mountains.

In 1520, Portuguese explorer Ferdinand Magellan would have seen a similar view as he led his Spanish fleet into the region. He travelled along a strait (later named after him) between mainland South America and a windswept archipelago he called Tierra del Fuego (Land of Fire) for the small fires he spotted along the shore. For thousands of years, the indigenous community here, the Yaghan, lit fires to keep warm and to communicate with each other. The flames burned in their forests, amid mountains, valleys and rivers, and atop the long canoes they steered over chilly waters.

Sixteen years ago, Cristina Calderon – one of the estimated 1,600 Yaghan descendants still living around their ancestral grounds – started the annual tradition of lighting three fires on Playa Larga in Ushuaia, a beach where ancient Yaghans gathered. Taking place every 25 November, the act recalls the Yaghan custom of lighting three fires to announce the arrival of a whale or a banquet of fish that everyone would eat. Releasing smoke signals was a way to convene the entire tribe, and it was common for them to share food and eat communally along the coast.

“The importance of the fire is more than something that brings us warmth in such a hostile place,” Victor Vargas Filgueira, a Yaghan guide at the Museo del Fin del Mundo (End of the World Museum) in Ushuaia told me. “It served as an inspiration for many things.”

An ancient word no-one can translate

An ancient word no-one can translate

That inspiration can be seen in a word that has garnered rapturous admirers and inspired many flights of the imagination. Mamihlapinatapai comes from the near-extinct Yaghan language. According to Vargas’ own interpretation, “It is the moment of meditation around the pusakí [fire in Yaghan] when the grandparents transmit their stories to the young people. It’s that instant in which everyone is quiet.”

But since the 19th Century, the word has held a different meaning – one to which people all over the world relate.

Magellan’s discovery of a ‘land of fire’ prompted more long-distance voyages to the region. In the 1860s, British missionary and linguist Thomas Bridges set up a mission in Ushuaia. He spent the next 20 years living among the Yaghans and compiled around 32,000 of their words and inflections in a Yaghan-English dictionary. The English translation of mamihlapinatapai, which differs from Vargas’ interpretation, debuted in an essay by Bridges: “To look at each other, hoping that either will offer to do something, which both parties much desire done but are unwilling to do.”

An ancient word no-one can translate

“Bridges’ dictionary records ihlapi, ‘awkward’, from which one could derive ihlapi-na, ‘to feel awkward’; ihlapi-na-ta, ‘to cause to feel awkward’; and mam-ihlapi-na-ta-pai, something like ‘to make each other feel awkward’ in a literal translation,” said Yoram Meroz, one of the few linguists who have studied the Yaghan language. “[Bridges’ translation] is more of an idiomatic or free translation.”

However, the word does not appear in Bridges’ dictionary – perhaps because it was seldom used, or possibly because he planned to include the word in the third edition of the dictionary, which he was working on before he died in 1898.

“It could be that he heard the word once or twice in that particular context, and that’s how he wrote it, because he wasn’t aware of its more general meaning. Or that it was only used in this more specific meaning that he quotes,” Meroz explained. “Bridges knew Yahgan better than any European before or since. However, he was sometimes prone to exoticising the language, and to being very verbose in his translations.”

Accurate or not, Bridges’ translation of mamihlapinatapai sparked a widespread fascination with the word that continues to this day. “The word got popularised by Bridges and was quoted and re-quoted in English-language materials,” Meroz said.

An ancient word no-one can translate

In many interpretations, the word came to signify a look between would-be lovers. On the internet, its definition is worded slightly differently as ‘a look shared by two people, each wishing that the other would initiate something that they both desire but which neither wants to begin’. Films, music, art, literature and poetry have all conjured its seemingly implicit romance and marvelled at its supposed ability to concisely capture a complex human interaction. The 1994 Guinness Book of World Records even listed mamihlapinatapai as the world’s most succinct word.

“The meaning is quite beautiful,” says a girl in the 2011 crowdsourced documentary Life in a Day, which portrays a single day on Earth. “It can be perhaps two tribal leaders both wanting to make peace, but neither wanting to be the one to begin it. Or it could be two people at a party wanting to approach each other, and neither are quite brave enough to make the first move.”

But what mamihlapinatapai actually meant to the Yaghans will likely remain a mystery. Now 89 years old, Calderon is the last fluent speaker of Yaghan, a language isolate whose origins remain unknown. Born on Isla Navarino, Chile, across the Beagle Channel from Ushuaia, she didn’t learn Spanish until she was nine years old. Meroz has visited Calderon several times to translate Yaghan recordings and texts. But when he asked her about mamihlapinatapai, she did not recognise the word.

“Most of her life, she hasn’t had many people to talk with in Yaghan,” Meroz said. “So if she doesn’t remember that particular [word] offhand, that doesn’t prove a whole lot.”

An ancient word no-one can translate

Will the obscure word be the sole survivor of a dying language?

“It used to be called a moribund language,” Meroz said. “I think these days people would describe it in more optimistic terms, especially the Yaghans themselves. There’s room for revitalisation.”

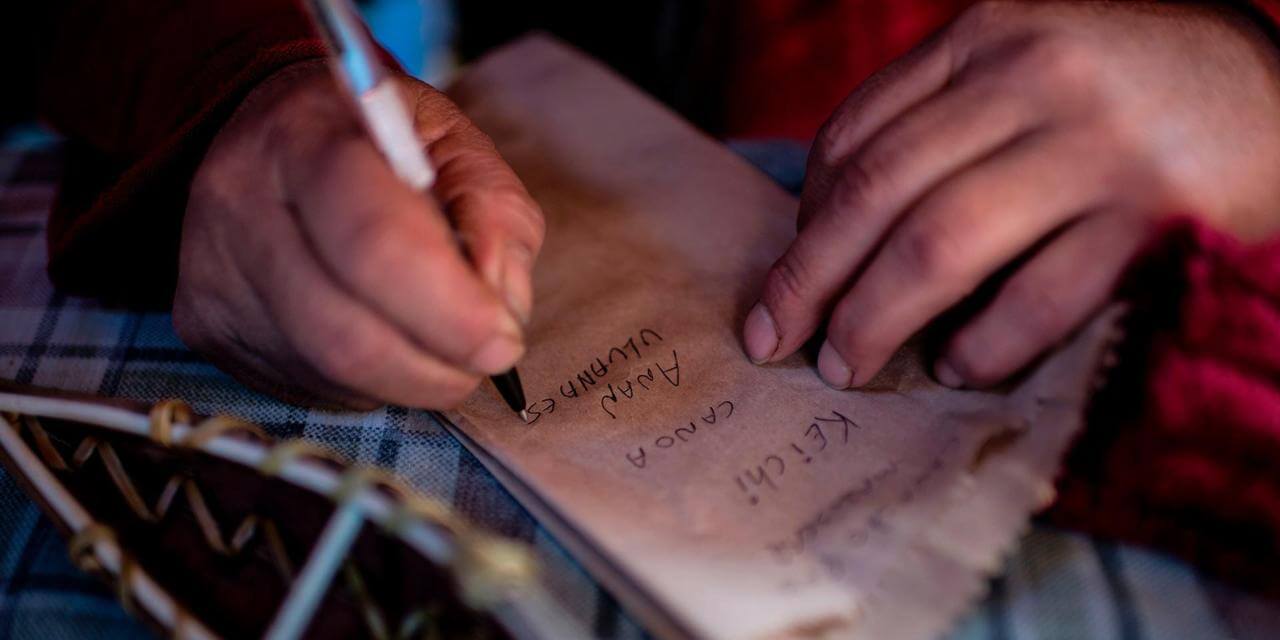

Calderon and her granddaughter, Cristina Zarraga, have led occasional Yaghan language workshops in Puerto Williams, a naval town on Isla Navarino near her hometown of Villa Ukika. Calderon’s children were the first generation to grow up speaking Spanish, as Yaghan speakers at that time were mocked. But the Chilean government has recently encouraged the use and maintenance of native languages, and Yaghan is now taught in local kindergartens.

“It’s nice to have a native speaker around to ask questions,” Meroz said of Calderon. “And there are always more questions to be asked.”

An ancient word no-one can translate

Many of the complexities of the Yaghan language trace back to how their ancient way of life intertwined with nature. Meroz recalled how Calderon described birds taking flight in Yaghan, using one verb for a single bird and another for a flock of birds. Similarly, there are different words for launching one or several canoes. There are separate words for eating: “a general word for eating, a word for eating fish, and a word for eating shellfish,” Meroz said.

In the 19th Century, as contact between Europeans and Yaghans became more frequent, new diseases decimated the population and the Yaghans lost much of their land to European settlers. Vargas’ great-grandfather, Asenewensis, was among the last Yaghans to live as the tribe had for millennia, searching the cold waters for food on his canoe and finding warmth and community around the fire. In many ways, he was the inspiration for Vargas’s book, Mi Sangre Yagan (My Yaghan Blood).

Vargas remembers listening to the language spoken by his family’s elders. “I watched the older Yaghans speak and cut into words with silence,” he said. “They spoke slowly, with pauses, making little sound. With few words, we say a lot.”

An ancient word no-one can translate

He often visits places where his Yaghan ancestors gathered along the coastline of the 240km-long Beagle Channel, which separates Ushuaia from Isla Navarino. The windy strait is speckled with rocky islands teeming with aquatic wildlife. Black-striped Magellanic penguins and orange-beaked Gentoo penguins waddle across the shore of the Yécapasela Reserve on Isla Martillo, oblivious to people nearby. South American sea lions and fur seals lounge on craggy coastlines.

At campsites around Ushuaia, Vargas lights fires on the ground and experiences what he believes to be mamihlapinatapai.

“It’s what I’ve felt many times with my friends far away in nature, around the fire,” he said. “We’re talking and suddenly there’s silence. That is the moment of mamihlapinatapai.”