Mongolia’s obsession with pine nuts

Halfway up the mountain, Enkhbaatar disappeared.

“Enkhbaatar, where are you?” We swivelled, trying to spot his white hat through the tangled branches. This was no place to lose one’s guide. We were only a few kilometres below the Siberian border, in a dense, subarctic pine forest known as a taiga. It was famously remote, even by Mongolian standards.

Mongolia’s surprising snack food

Thunk.

Something hit the ground near my feet and rolled down the slope. I looked up to see Enkhbaatar nearly 10m in the air, clinging to the top of a pine tree. He yanked an object from the swaying branches and pitched it toward us.

I skidded downhill, but Enkhbaatar’s six-year-old son got there first. He snatched up the fruit-like object and started to gnaw. Spitting out a mouthful of purple rind, he showed me the prize beneath: rows of yellow pine nuts. The local equivalent of popcorn or crisps, pine nuts are eaten uninhibitedly, by the bagful, because they taste so good.

Enkhbaatar tossed down a plastic sack for us to carry his haul. I knew pine cones as dry, squirrel-plundered husks; these were fat and ripe, with quilted skins like a pineapple. Their sticky sap glued dirt to our hands as we searched for more.

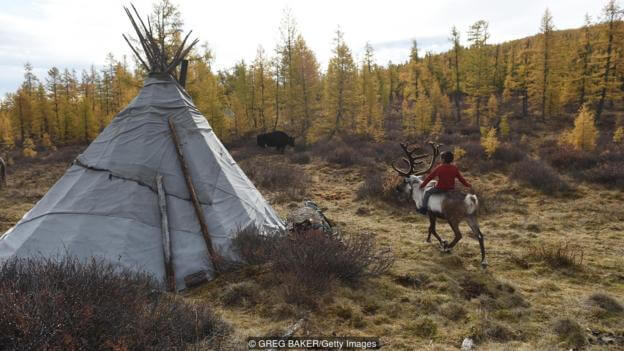

For me this was a novelty, but for Enkhbaatar it is daily life. He belongs to the Tsaatan, an ethnic minority who herd reindeer along Mongolia’s northern fringes. They live in tents alongside their animals and are essentially self-sufficient. Hunting pine cones in the taiga is the Tsaatan version of loading up on snacks at the supermarket.

Caught between tundra and desert, northern Mongolia’s agricultural options are limited; a severe climate renders much of the land infertile and restricts grazing. So Tsaatan families move seasonally with their herds to find pasture. They eat the meat, milk and cheese the reindeer provide, but their diet, with its abundance of protein and fats, lacks the vitamins and minerals usually obtained from fruits and vegetables. This nomadic lifestyle – and its culinary limitations – is typical throughout Mongolia and remains largely unchanged since the days of Genghis Khan.

Hunting pine cones in the taiga is the Tsaatan version of loading up on snacks at the supermarket

Pine nuts help balance the meat-heavy diet. They are rich in iron and vitamins A and D – common nutritional deficiencies in children across the country, according to The World Bank – as well as potassium, magnesium and zinc. Vitamin D is especially important; the deficiency pursues Mongolians into adulthood and causes a high occurrence of the bone-weakening disease rickets.

Mongolia’s surprising snack food

For the Tsaatan, the taiga ecosystem is a benefit of living along the nation’s isolated northern border; pine nuts cannot be found in the grasslands of southern Mongolia. Enkhbaatar’s family collects pine nuts every autumn to roast over the fire. They make a refreshing change from meat and milk; after a few days subsisting on salted mutton and reindeer cheese, the nuts tasted wonderfully clean and fresh to me.

Several months later in Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia’s capital city, deep winter cold had me yearning for that remembered flavour. Surprisingly, I didn’t have to go far to find it. Despite the availability of imported fruits and vegetables – not to mention fast food chains and coffee shops – city residents had a taste for pine nuts, too.

“They’re addictive,” my friend Byambaa told me as we walked the freezing streets. She wanted to get several kilos, but there weren’t any trees to climb in this glass and cement city. We needed a seller. While a few upscale restaurants offered pine nuts Western-style – sprinkled frugally over pasta – street vendors sold them by the bag.

Mongolia’s surprising snack food

As a kid in the forests of Khentii Province, located north-east of Ulaanbaatar along the Siberian border, Byambaa had helped her father clean, cook and sell pine nuts for extra income. Nowadays the business of selling the nuts requires permits and paperwork, and the majority of the harvest is exported to China. Mongolians can gather up to 25kg each year for their own use, but most rely on a supplier like Samjmiatav Azjargal.

We found Azjargal’s stand on a busy intersection near Ulaanbaatar’s downtown landmark, the State Department Store. It was a great place for foot traffic but terrible for the elements. In winter, Ulaanbaatar is the coldest and one of the most polluted capital cities in the world, and Azjargal was mummified in thermal clothes with a green scarf wound over her pollution mask. She topped up a steaming cup of aarts, a traditional soured milk, from a thermos as we discussed her wares.

She sells three varieties of pine nuts: raw, cooked and shelled. Like Enkhbaatar, she roasted them in a large pan over a fire – with no oil, salt or spices. The dried nuts took on a shiny brown quality, like coffee beans. They were displayed in heaps on makeshift tables and measured out in glass mugs. Transactions were swift – nuts scooped into a plastic bag, colourful tugrik notes changing hands – as passers-by sped towards warmth.

Mongolia’s surprising snack food

Azjargal’s husband and brothers spend the autumn season travelling through the northern provinces of Khentii, Selenge, Khovsgol and Zarkhan to pick pine cones. Sometimes they bring the whole family, turning the expedition into a camping trip. She pulled out her phone to show us photos from this year’s harvest; the green, sunlit pictures pulled me out of Ulaanbaatar’s cement chill and back to my memories of the taiga.

According to Azjargal, all that tree climbing by Enkhbaatar had been unnecessary. Pine nuts had just come into season when I visited the taiga in August; by mid-October, the cones would have been ripe enough to literally shake off the trees. But there are more than hungry squirrels to contend with. Pine nuts are big business these days, and many people start early to get ahead of the competition. Azjargal confided that she had also begun in August, allowing the nuts to ripen in their cones for several weeks after being picked. Stored in a dry place they would last all year.

Mongolia’s surprising snack food

Azjargal bagged our order, apologising for her prices. It had been a bad harvest, she said, and roasted nuts were up to 13,000 tugrik (roughly $5) per kilogram from last year’s 8,000 ($3). Shelled were three times more expensive, so most people preferred to bite the nuts open themselves and spit out the shells, the way Americans eat peanuts at a ballgame. According to Azjargal, good harvests come in a three-year cycle, and she expected prices to stay high through next winter. I didn’t complain; a kilogram of shelled pine nuts costs $60 in the United States, where I’m from.

Handing over my bag, Azjargal suggested I steep the nuts in vodka. The infused liquor, she said, is good for women’s health. Instead, Byambaa and I decided on coffee to warm up. We opened the bag of pine nuts, and a pile of empty shells grew between us on the cafe table. The cooked nuts were milder than the ones I’d eaten raw with Enkhbaatar. They had a soft texture and tasted lightly of almonds. And Byambaa was right – they were addictive.

Outside the window, Azjargal nimbly kept up with demand. Knots of school children, women wrapped in expensive furs, mechanics in grubby pants – everyone stopped for a snack on their way home. Given a choice between a bag of crisps in a heated store and chilled pine nuts from a near-frozen street vendor, Mongolians know there is no contest.