After 100 hours in Tibet, I knew it was time to leave

After 100 hours in Tibet, I knew it was time to leave

Writer Pico Iyer understands that by keeping an outer journey short, you can make the inner journey that follows echo across a lifetime. In time, like space, a curious mathematics often takes hold. The fewer things you have in your memory, the more space each one has to reverberate inside you. A brief trip can be like an empty room in a Japanese tea house: if there’s nothing there but a single scroll, that scroll becomes the universe. Sometimes, I’ve found, it’s only by keeping an outer journey short that you can make the inner journey that follows echo across a lifetime.

I wasn’t thinking any of this consciously when my plane from the Chinese city of Chengdu touched down on a deserted airstrip miles from Lhasa, the longtime capital of Tibet, in September 1985. The opposite: I was a kid in his 20s playing hooky from my 25th-floor office in Midtown Manhattan, where I was writing articles on world affairs for Time magazine. I’d managed to escape from my office on a six-month leave of absence, and soon after arriving in China, I’d become aware that Tibet was now open to foreigners, really for the first time ever.

I’d first gone to see the Dalai Lama in his Indian home in Dharamsala as a teenager – thanks to my philosopher father, who’d met the Tibetan leader months after he came into exile in 1959 – and I’d been following the situation there from afar. But now the government in Beijing had opened Tibet up to foreign tourists, and I couldn’t resist the prospect of being part of the first wave of visitors.

What it means to know when to leave

As I stepped out into the thin air, however – the air so shockingly blue – I wondered if I’d succumbed to one Shangri-La myth too many. The few other foreigners on the unsteady Chinese commercial carrier looked like renegades: scarf-swathed adventurers; pantalooned ne’er-do-wells; scientists in cowboy hats on missions they refused to disclose. Our congregation of the curious was herded towards a battered bus, and very soon we were jolting across roads and over streams on a journey to Lhasa that never seemed to end.

There were few signs of what I thought of as civilisation along the road: only some small statues outside of caves and Buddhas painted in dazzling colours on the rocks. Occasionally we passed a pilgrim, grimy with hundreds of days of travel, joining his palms before him and then falling into the dust, again and again, in a devotional three-part prostration of prayer. When at last we pulled into a ragged courtyard, the ‘City of the Sun’ disclosed itself as a little town of whitewashed houses gathered around the ancient Barkhor market area, with flower boxes golden under deep blue skies, worn prayer flags flapping under white open rooftops.

What it means to know when to leave

I knew a bit about Tibet, I thought. I’d devoured such classic works as In Exile from the Land of Snows and Seven Years in Tibet. I’d once even dragged 16 colleagues from Time’s World Affairs section down to the dingy basement of the now-defunct Tibetan Kitchen restaurant on New York’s Third Avenue to school them in Himalayan realities. But what I saw now was nothing like what I’d read about in Alexandra David-Néel’s mystical account, Magic and Mystery in Tibet.

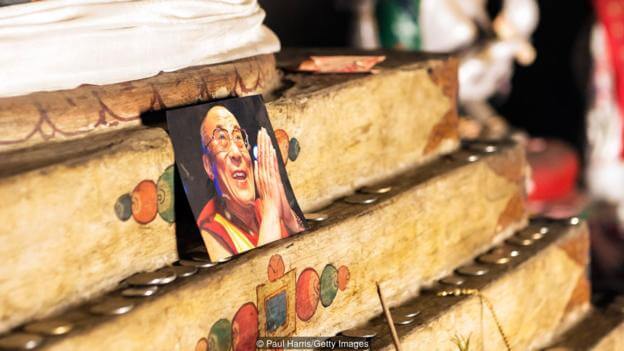

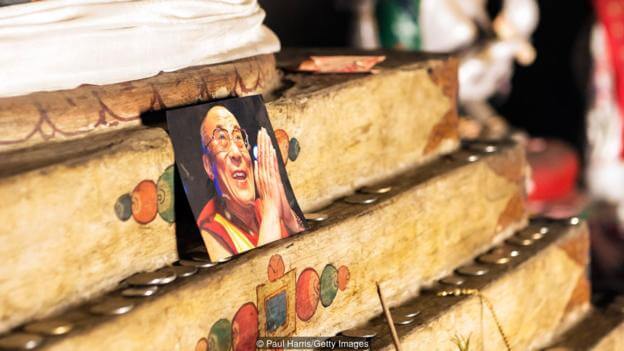

Men were circling around the main square in front of the Jokhang Temple, muttering under their breath, ‘Dalai Lama. Dalai Lama’, in the hope that a foreigner might slip them a contraband photo of their exiled leader. Undercover policemen roamed here and there across the plaza. Everywhere, nomadic Golok women in green bowler hats, huge Khampa warriors with red thread in their long hair and purple-cheeked kids by their side were circumambulating the temple, spinning prayer-wheels as they walked, while workers sang folk songs as they laboured to restore crumbling buildings.

I’d read, back in Midtown, about a new hotel on the far side of town, so I trudged along to it, hoisting a suitcase almost bigger than I was. When I arrived, it was to find what might have been a spectre’s hospital of empty rooms, an oxygen tank beside every bed. I turned around and started padding back – no-one had told me about altitude sickness. Brilliantly smiling yak herders shouted things at me I couldn’t understand. Scratchy country-and-Eastern music – nomad songs delivered by a single bare voice against a single plucked string – crackled out of cassettes in roadside stalls. Tibet was so undiscovered then that it offered scant footing for a foreigner.

What it means to know when to leave

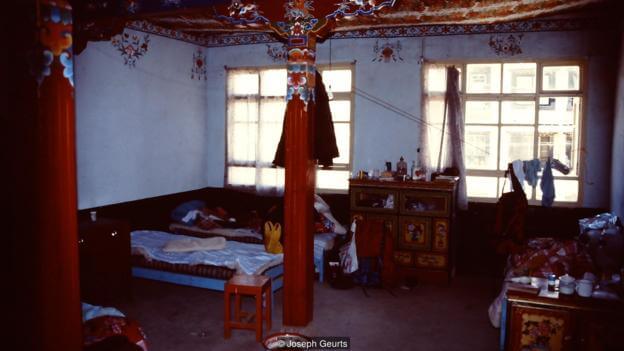

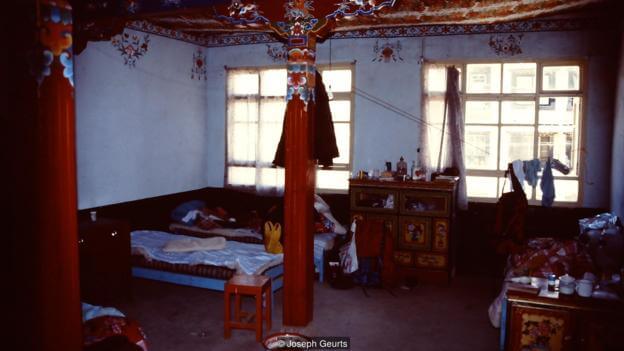

At last I saw what looked like some Europeans marching along the main drag, and I slipped into the dark entrance that they’d emerged from. ‘Banak Shol Hotel, Happiness Road’, read the sign. A young Tibetan with a smattering of English told me I could have a room for $2 a night. A room was all it was: a large bare mattress with a straw pillow, and no space even to move. A filthy shared toilet lay at the end of the outdoor corridor; a rusty tap in the courtyard below offered water.

I teetered my way up a steep wooden ladder, dropped my suitcase off in my dark, airless chamber, then went out again and slipped through a labyrinth of muddy alleyways to the Jokhang (which only a few weeks ago erupted in flames). In front of it, monks and nomad women, tiny toddlers and their grandmothers, were performing three-part prostrations as, I’d see, they did from dawn to midnight. When I entered the temple, I could catch little by the dim light of flickering candles. But soon I could register tears streaming down the roughest Tibetan cheeks as petitioners shuffled forwards, past one god of compassion and wisdom after another, stunned to have attained at last the holiest place in their holy city.

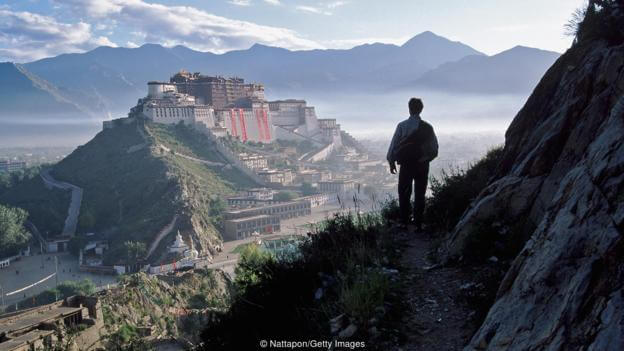

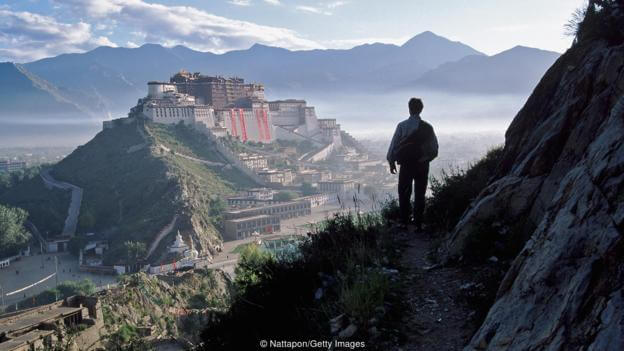

Next morning I travelled out to Ganden, once one of the largest monasteries in the world. Now it was just a jumble of broken stones. Three red-robed monks enjoying a picnic in the dirt waved me down to join them in salted yak-butter tea and rough bread. On the bus back, a fist fight broke out as a group of Tibetans gathered around a lone Chinese, a reminder of how even the occupiers were at times a victim of their circumstances. After night fell, I noticed that the whole small town sat under the protective gaze of the 13-storey Potala Palace up above, only a few lights gleaming from its more than 1,000 rooms.

What it means to know when to leave

In the pre-dawn dark the next day, I walked for an hour away from the buildings, past the yak-hair tents of nomads, solitary candles outside them, until I arrived at a faraway crag where sturdy Tibetans were engaging in a grisly ritual practice: chopping up a fresh human corpse, in the traditional way, to feed to birds of prey. It felt somehow like an invasion – a holy rite being devoured by us uncomprehending tourists – and yet not to see a ‘Sky Burial’ seemed a kind of sacrilege.

In the afternoon, I went out to Sera and Drepung monasteries, recalling the stories my professor father had told me of their skull-filled murals and ritual debating with 20,000 in attendance. At this moment, there were mostly dogs seated patiently in courtyards and a handful of young novice monks asking to play with my camera.

Finally, on my third morning in the city, I made the long climb along a zigzagging path to the Potala. Following a group of Tibetans to a dark booth in the first courtyard, I parted with a few pennies to purchase two religious scrolls swarming with deities and visions of the universe. I went up into rooms through which shafts of high sunlight were streaming, as monks sat in corners between red and golden curtains, reading from the sutras. There were statues and treasure halls at every turn; women were bowing to receive blessed water from monks amid relics of the nine Dalai Lamas who had lived there.

What it means to know when to leave

At one point I stepped out onto a whitewashed terrace to look across the valley to the mountains, which were dusted with fresh snow. The sky was cobalt, and everything came to me with a sharp, zoom-lens immediacy. I couldn’t say why, I couldn’t say how, but somehow, as I stood there, I felt not just on the ‘rooftop of the world’ mentioned in all the brochures, but on the rooftop of my being – some clearer, stronger state of mind I didn’t recognise.

Maybe it was the thin air. Maybe culture shock or the accumulated weariness of the succession of flights and the bumpy bus ride. Certainly, I wasn’t eager to feel anything special in the land that so many associate with otherworldly transports. I recalled how Sir Francis Younghusband, the British soldier who led a murderous expedition on the city in the winter of 1904, had gone for a long ride on his last afternoon in Lhasa. Whatever he experienced there was so strong that he doffed his soldier’s uniform, returned to Europe and became one of the century’s most fervent peace campaigners.

In my 20s, I was foolish enough to believe that you fashioned yourself by not thinking what other people thought, and defined yourself by everything you thought you could see through. As a hard-headed journalist for Time, I considered myself averse to clichés. But as I stood in that high, clear light, transported almost in spite of my best efforts, I made a promise to myself as never before or since. I would leave two days later, after only 100 hours in Tibet, so that my stay in Lhasa would always make a clear whole in my head. These were days of heaven I would never know again, so I’d depart as soon as possible and keep the interlude forever distinct in my head.

What it means to know when to leave

I’m embarrassed at who I was in my 20s now, so quick to pass judgment, so hemmed in by schoolboy scepticisms. But in that one moment my instincts were true. I left Lhasa after only four days, and, 33 years on, every hour of that stay feels as picked out as a solitary canvas in an enormous banquet hall. I’ve returned to the Tibetan capital more than once, I’ve spent years travelling across Bhutan and Ladakh and Nepal, as well as at similarly displacing altitudes in Bolivia and Peru. But I was right: what I felt that moment, I’ve never felt again.

Now, as I sit at my desk and take the trip once again, I’m reminded how it’s always in an empty room that I feel fullest. Part of the challenge of any outer journey, especially when exalted, is having the courage to know when to cut it short, if only so that the inner journey can – and will – remain alive, distinctive and whole, forever.